Internet Explorer 9, the HTML 5 browser: Better than half-way there

Offloading processing to the background and to the GPU

The architectural development that helped Firefox and others vault from banana-like bars such as those on the left of Microsoft's SunSpider chart, to peanut-like bars like those on the right, was the implementation of just-in-time compilation (JIT) -- a concept first implemented in Java and .NET, re-engineered for JavaScript. Today, Hachamovitch's tactic was to characterize JIT compilers as "JIT-ters," complete with the wimpy sound and unstable connotations, similar to how AMD characterized Intel's introduction of "hyperthreading" five years ago.

"In the beginning, the Web had lots and lots of HTML, and little pieces of script here and there. And an interpreter was good enough for that. Over the years, different browsers have added JIT-ters and different kinds of JIT-ters, many different kinds of JIT-ters. The problem with JIT today is that so much time and energy goes into managing the time and scope that the JIT-ter operates in. Users have to wait if the JIT-ter JITs too much, because the JIT-ter is sitting there compiling the code, and you don't get to run it. And the user has to wait if the JIT-ter JITs too little, because then the JIT-ter did a little bit, and the user is stuck running a slower interpreter."

Something vaguely similar to the phenomenon Hachamovitch described is what we at Betanews have seen in a recent round of high-level browser testing, on IE and other platforms, in preparation for today's release of the IE9 tech preview. JavaScript interepreters, by today's design, are single-threaded. Their ability to run JavaScript very fast depends, to a great extent, on the relative complexity or simplicity of the instructions. JIT compilers produce much simpler machine code, but only in situations where the JavaScript instructions are relatively simple to parse, and not entangled in competing loops with unsightly timeouts. Long stretches of uniform code -- 100,000, one million, even ten million iterations -- are like butter candy to browsers like Chrome, smooth, silky, and easy to digest. But break up those instructions with interruptions (for instance, updates of an on-screen timer at one-second intervals), and what once seemed like butter now processes like rock-filled concrete. And sequences that Chrome could execute in under 30 seconds, all of a sudden, could take (by my estimate) days to execute if left unattended.

It's in situations like this where the JIT-ter is jittering, to borrow Dean's phrasing. But about the only place you're going to find someone trying to do 10 million iterations of an algorithm in succession, is at Betanews, where the guy doing the testing is on his sixth cup of coffee and is jittery anyway.

Still, in anticipation of the types of advances Dean described today, we've been working to create a new class of tests that would enable IE9 to shine if it truly does what Dean says it does. Today, he described how IE9 moves the JavaScript interpreter to a background process:

"Compiling in the background puts hardware to use here without having to re-code the site. And the key here is to bring the best technology to the most important language you use, JavaScript."

HTML 5 in large print, SVG in small print

HTML 5 in large print, SVG in small print

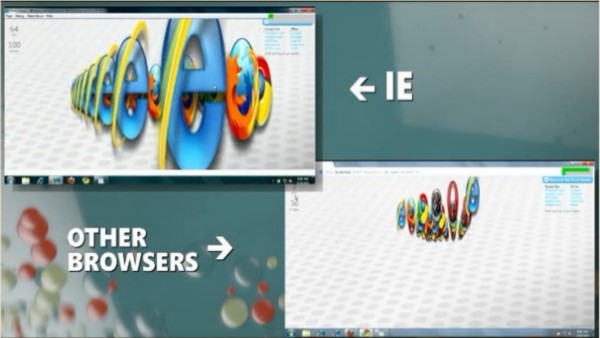

Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG), a W3C standard since 1999, has never been actively supported by Internet Explorer even to this day. During today's demonstration of what he called, on the surface, "HTML 5 applications," Microsoft's Dean Hachamovitch was joined onstage by Windows Division President Steven Sinofsky to jointly demonstrate the IE9 technical preview's new GPU-assisted graphics rendering support, with Sinofsky on the new browser and Hachamovitch playing catch-up with Chrome.

Tucked away in the background of that clever little duel was the fact that IE9 was, for the first time, directly and openly supporting SVG.

It's difficult to see from the screenshot of Microsoft's presentation above, but Sinofsky's IE9 browser at the upper left is rendering 100 simultaneous 3D extrapolations of 2D logos from various browsers, at 64 frames per second. Hachamovitch's Google Chrome, meanwhile, is rendering about 36 simultaneous logos at about 8 fps.

HTML 5 may have had little or nothing to do with this result. The real takeaway from this demo is the following: For years, Web developers have relied on Adobe Flash for vector graphics that are scalable, mainly since it's the only platform that can be plugged into all the major browsers and that can run uniformly within all of them. The reason for that is IE's reluctance to embrace SVG. Well, now that embracing SVG is necessary in order for Microsoft to demonstrate its graphics processing prowess, this could change the ballgame for Web developers, who may soon have at their disposal, at long last, a single open standard for animating Web sites.

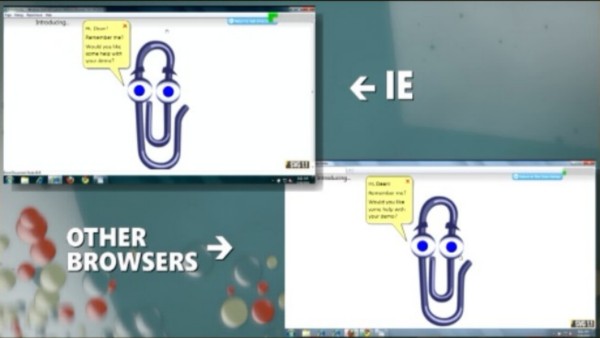

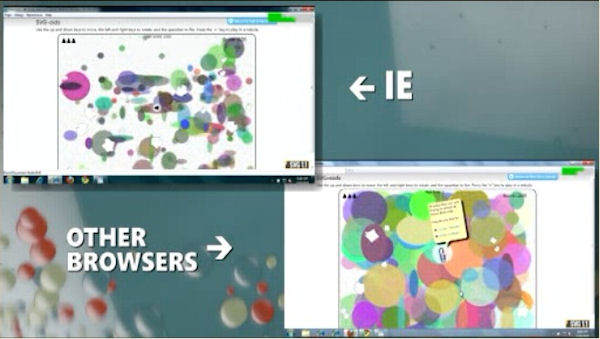

Who better to celebrate that news with than the lovable Clippy character we all adored from Office XP? In a demonstration not only of processing prowess but of standards compliance, the two executives enlisted Clippy as the hero in a 3D game of Asteroids, where the targets were multi-colored circles of translucent plastic. Rendered properly, Clippy could hold his own; but stuck in Google Chrome, which doesn't appear to apply relative opacity properly, it looks like Clippy may be in trouble. And it looks like he's writing a letter of distress.

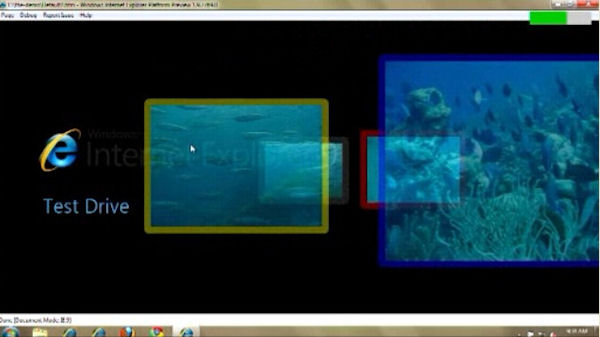

Microsoft has posted links to the tests Sinofsky and Hachamovitch demonstrated on stage, on its special site devoted to the IE9 developers' preview. There you're also likely to find the stunning IE9 video carousel, which HTML 5 has everything to do with. Here, four HD videos of underwater scenes are rendered on translucent screens, that simultaneously travel along an invisible carousel-like path. Of course, you may always have known this kind of rendering power existed in your GPU, but you might never have seen your Web browser go this far to exploit that power.

The IE team has always been careful to say that the advances that matter are the ones that users see and feel. Last year, the company advanced the argument that millisecond differences were imperceptible. Which they are, unless they become fruitful and multiply -- and in a Web applications environment, that will happen. The news from Las Vegas today is this: Microsoft is building a Web applications platform. Finally.