Broadcast radio one step closer to paying performers' royalties

With the music industry's business model in flux, mostly due to forces seemingly beyond its control, one way of potentially reducing some of the stress from lost CD sales is by Congress lifting terrestrial radio broadcasters' exemption from paying royalties to musical performers -- an exemption that has been allowed since the beginnings of radio. Though a majority of representatives in the US House have voiced opposition to such a measure, a similar majority has yet to coalesce in the Senate.

Yesterday, concerted leadership in the Senate Judiciary Committee passed its version of a bill authored in the house by Rep. John Conyers, Jr. (D - Mich.), effectively striking language from US Code granting radio broadcasters exemption from paying royalties to performers. (Broadcasters currently do pay royalties for copyright holders, typically through annual fees.)

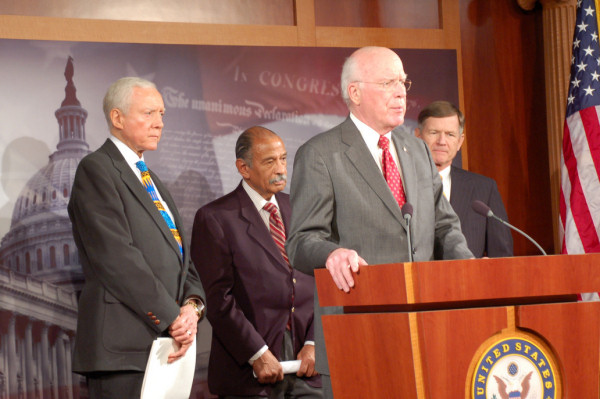

"Radio play surely has promotional value to the artists, no one is denying that," said Sen. Patrick Leahy (D - Vt.) on the Senate floor yesterday. "But there is a property right in the sound recording, and those that create the content should be fairly compensated for their work."

An amendment added to the Senate bill yesterday by Sen. Al Franken (D - Minn.) sets alternative minimum royalty rates for stations earning as little as $50,000 per year. And another amendment attached by Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D - Calif.) -- so new that it hasn't yet appeared in the Library of Congress' transcript -- would establish, as Sen. Leahy's office puts it, "parity in the rate standard across platforms that publicly perform sound recordings." In other words, a mandate for equal rates between the fees broadcasters will pay, and what Internet radio streamers such as Pandora agreed to pay in a compromise last July.

That could mean a whole new ballgame for copyright holders as well. As it stands now, broadcasters use a relatively simple formula to pay copyright holders for the use of the composition, as opposed to the use of the recording. That fee is based on a total cap on receipts of $230 million per rights organization (PRO) per year, divided by the number of radio stations participating. But as broadcast law expert David Oxenford writes, that fee is set to expire at the end of this year, and the renegotiation will not be easy.

Making it easier -- at least on rights holders -- would be that congressional parity mandate. If in the sake of "fairness" broadcast radio is held to the same standard to which Internet streamers agreed, the formulas for both performance and recording royalties could become adjusted to reflect a percentage of each station's revenues. Currently, streamers have agreed to a complex system whose ballpark basis is that the sum of performance and recording royalties be capped at 25% of net revenues, from any and all enterprises associated with the music, including advertising.

Whether the US radio industry could sustain such an expense, if it balloons this high, is doubtful. Industry analysts estimated that the total revenues collected by the nation's 12,500 stations dipped below the $17 billion mark last year, and will decline by at least another 10% by the time this year is out. If those estimates hold out, performance rights organizations under new legislation could stand to split not $230 million, but as much as $3.8 billion.

With 251 out of 435 representatives opposed to such legislation, according to the National Association of Broadcasters, you would think that should end the issue. But legislation that doesn't stand a chance of succeeding by itself has ways of getting passed anyway, usually as riders to unrelated bills that have no chance of failing. Health care legislation is already a complex issue; with the President's desire to get such legislation passed before the holidays, it could find itself taking on a passenger.

Which would be convenient for PROs, whose current agreement with stations expires after December. Station owners have intimated that should such new rates go into effect, they may stop playing music altogether and switch to talk-radio formats. And that would be convenient for politicians needing new platforms for assailing other politicians.