Mozilla aims to revolutionize Web layout with new Firefox font support

One area of Web standards where both Mozilla Firefox (version 3.5.3 CRPI: 7.34) and Opera (version 10 CRPI: 6.38) have an edge over Google Chrome (build 3.0.195.25 CRPI: 15.85) is in the field of page-designated font rendering. It's where the code for the Web page specifies which fonts to use, and even triggers the downloading of those fonts where necessary. Actually, Opera 10 has led the way in scalable Web fonts support although Firefox 3.5 has followed close behind.

The problem here has been with the extremely proprietary nature of the fonts used for the Web. They actually are TrueType and OpenType fonts, the majority of whose licensing prohibits their use for anything other than installation in commercial operating systems on a per-desktop basis. Even though some typographers have created free renderings of their commercial font products (here's a favorite of mine: Museo Sans by Exljbris), there's some question as to whether type designers are technically allowed to use the proprietary underpinnings of font technology (mostly contributed by Adobe, Microsoft, and Apple) for use on the Web.

Now, in an effort to resolve this little dilemma, Mozilla is announcing that forthcoming daily builds of version 3.6 (presumably the Beta 2 Preview editions) will support CSS3 @font-face embedding using a font format that is not TrueType or OpenType. It's being called Web Open Font Format (WOFF), and its purpose is simply to repackage the same spline data that appears in TrueType and OpenType font files, in a format and with licensing that's tailored exclusively for use on the Web.

Leading the move toward WOFF is Mozilla contributor Jonathan Kew. In a document Kew co-authored for the W3 Consortium, he writes, "A WOFF font file is simply a repackaged version of a sfnt-based font in compressed form. The format also allows font metadata and private-use data to be included separately from the font data. WOFF encoding tools convert an existing sfnt-based font into a WOFF formatted file, and user agents restore the original sfnt-based font data for use with a Web page." (Here, "sfnt" refers to a specific type of spline geometric data, and is a term based on how early Macintosh systems tagged spline data appearing in OpenType files.)

The metadata will enable foundries to include licensing information which could, for example, restrict a downloaded font's ability to be used anywhere on the user's system except on the page that triggered its download. Or, it could enable an open font intended to be used multiple places, to be shared freely.

What WOFF could also enable -- as part of a future wave of developments that could be ready for Firefox 3.7 next year -- is for Web designers to use the variations that are present in font files, but which HTML and even CSS have never directly covered: Many fonts include hints for how renderers should typeset small caps, and how it handles ligatures -- like connecting capital "T" with small "h," or small "f" with small "t." Without a mechanism in place for addressing the special capabilities of many fonts, CSS can't get a handle on them.

What WOFF could also enable -- as part of a future wave of developments that could be ready for Firefox 3.7 next year -- is for Web designers to use the variations that are present in font files, but which HTML and even CSS have never directly covered: Many fonts include hints for how renderers should typeset small caps, and how it handles ligatures -- like connecting capital "T" with small "h," or small "f" with small "t." Without a mechanism in place for addressing the special capabilities of many fonts, CSS can't get a handle on them.

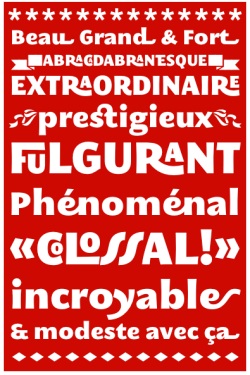

So Mozilla engineers proposed an amendment to CSS just last June 29: a new property called font-variant that enables exclusive properties of embedded fonts to be declared outright. In a build of Firefox 3.6 that was altered by Kew for testing this feature, he was able to produce the lavish typographical poster you see here, using a font called Megalopolis by Jack Usine that's rich with ligatures, using only HTML.

With full font features enabled, diacritical marks, monospaced numerals, and capital letters and descending lower-case characters with sweeping swashes only where applicable (like the beginnings of sentences), would all become addressable by browsers, making them effectively the typographical layout engines that engineers always knew they could be. The result could be a Web where usable text may appear as clearly as on the printed page.

The biggest hurdle the Mozilla engineers may face with this feature is a familiar one: contending with Microsoft's Internet Explorer trying to implement the same feature, but in a different way. As Mozilla contributor Christopher Blizzard acknowledged in a blog post yesterday, "IE currently tries to download all fonts on the page, whether they are used or not. That makes site-wide stylesheets containing all fonts used on site pages difficult, since IE will always try to download all fonts defined in @font-face rules, wasting lots of server bandwidth."