What hath Mac wrought? A remembrance after a quarter-century

The world that made the Mac

When younger folks today (I don't have to pretend I'm old enough anymore) ask me what it felt like to experience a Macintosh for the first time, expecting a moment of revelation as though I'd set foot on Mars, it's hard for them to understand this embryo of the Mac in the context of the world we early developers lived in. While we appreciated the Apple II for having accelerated the pace of evolution in computing, and for having been smart enough to let people tinker with its insides like with the Altair 8800 a mere three years before the II premiered, most of us in the business had the sincere impression that Apple least of all understood what our work was about. The Apple III was proof -- the only way it could run good software was when it could step down into Apple II emulation mode. And the Lisa didn't even have that.

What it did have was Motorola's 68000 processor, and now we could really see what a world of difference it would eventually bring to our lives. Back in the early '80s, the CPU ran not only the operating system and the software but whatever graphics the software was capable of doing -- it wasn't shipped off to some co-processor. Simply watching the mouse pointer move fluidly on the screen was impressive to us at the time -- more amazing, even, then creating our first plaid-patterned polygons with LisaDraw for no particular reason.

But also, the world of computing was full of so many more great names than today. Sure, IBM was marching in and would set the tone for the next few decades, but we still had Commodore, Atari, Osborne, KayPro, Ohio Scientific, HP (which had its own designs for business computers at the time), Exidy, Sinclair, Apollo, and the brand which brought me into this business in the first place, Radio Shack. The world was full, and new ideas in hardware were coming out everywhere. Sure, some geniuses in particular rocked the world, but from our vantage point, that's what everyone was doing...that's what we were doing. Steve Jobs was one of our rock stars, sure. But we had a plethora of others -- Jay Miner, Adam Osborne, Chuck Peddle, Clive Sinclair; the writers like Rodnay Zaks and Peter McWilliams; the great publishers we loved (some whom I'd later work for) like David Ahl, David Bunnell, Wayne Green; and the brilliant man whose name is so long forgotten, but who may have contributed at least as much if not more to our foundation of computing than anyone else, Gary Kildall.

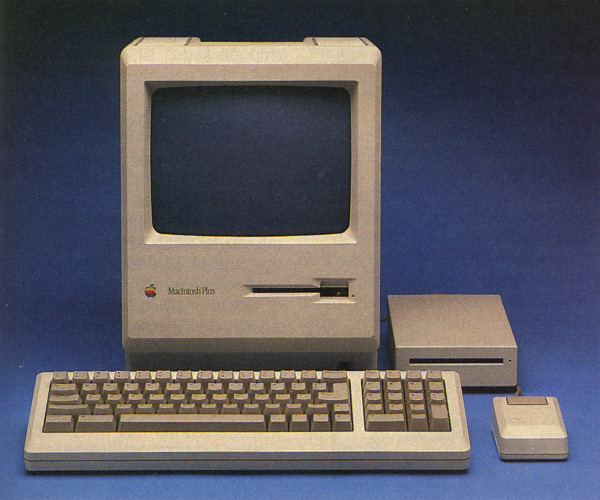

It started to come together with the advent of the Macintosh Plus, with 512K -- enough memory to actually run software -- and the numeric keypad.

So when the Macintosh first entered the scene for us, you have to understand, "new" for us came every three months or so. Even then, some of us were still puzzling over the Lisa. Though we all loved the "1984" ad, our expectations of the first Mac were based on our supposition that it would be an attempt to correct the failures of the Lisa. Being priced $8,000 less certainly helped.

But even the first Macs weren't brilliant, not really. They suffered from what we all perceived to be Steve Jobs' basic nature to go with whatever he had at the time, explaining that it's all by design, and if we didn't get it, then it's our fault. The first Mac was a closed system -- oh sure, it had a serial interface that was being "pioneered" by Apple, for the connection of external devices that we were promised but never actually saw. But we couldn't get hard drives to work with the first Macs, no matter how hard we tried (SCSI would only come later). The very first Mac-only conferences, sponsored by the nation's Apple II users' groups -- easily the most friendly and the greatest computer users who ever walked this planet at any time in our history -- were literally showered with businesses whose missions were to connect real peripherals to these things. We had laser printers, for crying out loud, and they were beautiful, but we had to fit our documents on these floppy diskettes; and without compression, we were using one diskette per document easily.

And because opening up one's Macintosh to do something horrible and unsanctioned, such as hiding a hard disk, constituted a violation of the sacred and sacrosanct Apple Warranty, none of these businesses were given accreditation by Apple, and many of them were scared to even employ the Apple logo in their brochures for fear of retribution. Thus the first Mac users' groups -- the offshoots of the Apple II groups -- flourished despite Apple. In fact, at about the time he was ousted from his CEO position, many leaders of the Apple community were tired of Steve Jobs and his bloviating nature, and were more than happy to see him replaced with the down-to-earth, all-business, no-frills approach offered by John Sculley.

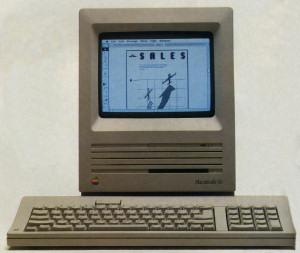

Throughout the duration of the 1980s, the Macintosh was never the most powerful 68000-based computer you could buy. In terms of raw processing speed, the Atari ST (the focus of my career for about four years) blew the Mac away in every single challenge, yet that computer was being peddled by a company that was as clueless about computing as FEMA was about hurricanes. And for sheer fun and excitement and creativity, the Commodore Amiga ran circles around the Mac at warp speed. Both the ST and Amiga had orders of magnitude better software going into 1987. Meanwhile, the world's best software authors all wanted to write for Mac and were stymied by all the hoops Apple made them jump through just to be certified, to get development kits, to attend the seminars, and to be treated in kind. Then something happened round about 1988, in the era of the Mac SE and the Mac IIci, when the 68020 and 68030 processors roared to life. The software got better, the systems became more reliable...HyperCard entered the public vernacular. And Apple became more desperate, more humble, and more willing to let other companies enter into its realm. There was an opening, for the first time. System 7 took bold steps forward in functionality and principle. It really took five long, painful years for the Mac to truly be born.

Indeed, the Mac's greatness derives from its designers' willingness to break barriers. Not everything they tried was novel, and let's face it, a good deal of it (just like Windows) was stolen from someone else. Many of the concept's original ideas fell flat on their face, which is the key reason none of us boot up with Workshop disks today.

The first great Macintosh: The Mac SE

The true brilliance of Macintosh is the ideal that computing can have one way of working that we can believe in and stick to. That brilliance was inside the crate the Lisa was delivered in, but it may have been too hard to notice on day one, when I flipped the switch for the first time. Back in the late '70s and early '80s, when systems crashed, we lost everything we were working on, and sometimes the disk it was stored on; even the Lisa brought forth the idea that an operating system can be all-encompassing, that you could be "in" the Lisa rather than "in" dBASE or VisiCalc or Valdocs. The computer itself could define the way its user worked.

Granted, that was a great idea that was probably born in Gary Kildall's mind before anyone else's, but Apple made it work first. It took a lot of time and patience, and some swearing -- most of which has been forgotten by revisionist history. But if you were there in the room when the switch was flipped, or if you can imagine sitting there on a folding chair and watching it happen and sharing the joys and the frustrations in equal measure, then you can truly appreciate what the Mac has brought us.

[Photo credits: Scans of the Macintosh Plus (1985) and Mac SE (1986) from Byte Magazine]