2006: Google considered a PR campaign against content owners' 'foot-dragging'

In what may have, by now, become an exercise in the airing of corporate dirty laundry (or, in some cases, not even dirty), Viacom yesterday released more evidentiary documents from its court battle with Google. This second round of what was promised to be three public releases (though there could be more to come) includes confidential Google executive presentations from the period prior to its acquisition of YouTube, when the company was considering instead bolstering Google Video to become more competitive.

Rather than being incriminating, the documents paint Google executives to be cunning, shrewd, and eager to assume the mantle of the moral high ground. But they also reveal instances where the company considered pressing its high-ground position to its advantage, with prospective PR campaigns and likely incentives to the press that would encourage the viewpoint that media companies such as Viacom (parent of Paramount Pictures and MTV Networks) were behind the times, inflexible, and unwilling to open up their content vaults for fair use.

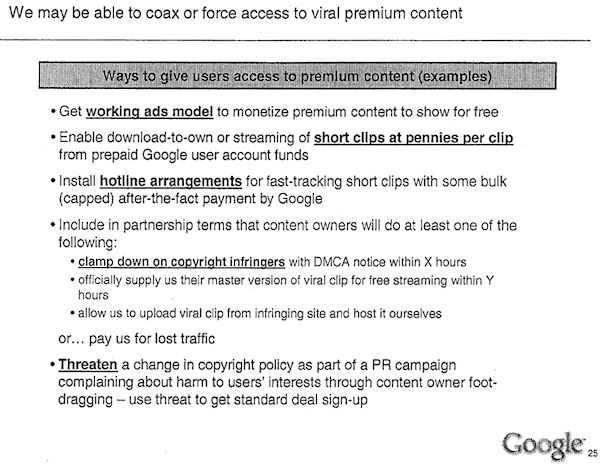

One bullet point recommendation for consideration from a June 2006 presentation on strategic directions for Google Video, concerned the use of a PR campaign to coerce media companies, explicitly including Viacom (whose logo appeared on one slide along with others'), to make more "viral" video available for premium (paying) users. "Threaten a change in copyright policy as part of a PR campaign complaining about harm to users' interests through content owner foot-dragging -- use threat to get standard deal sign-up," the suggestion read.

A slide from a 2006 Google executives' presentation showing they considered retaliating against content owners with a press campaign. From documents released April 15 by Viacom.

Although a Viacom press statement yesterday accused Google of "explicitly advocating that Google use the threat of copyright theft to advance its business interests," a closer read of the presentation in its entirety, and an understanding of the context in which it was made, suggests another interpretation: Google may have been considering the implementation of a new policy whereby content owners such as Viacom would have been more directly responsible for material that users may have uploaded, forcing them to more publicly prohibit the specific use of certain clips or segments of video. Imagine how Viacom might have looked if they had to post a public message saying, "You can't watch clips from Iron Man yet," on a big public display. Google would develop a "review tool" to help premium content partners scan the system for clips from Iron Man and other properties, but in the absence of action on the partners' part, Google would compel the press to publish articles that paint partners as dinosaurs.

Again, this is not what Google actually did -- as we all know, Google acquired YouTube instead. But this examination of the strategy the company could have used to combat YouTube -- a strategy which may very well have actually worked -- demonstrates the kind of template that Google uses when framing a corporate strategy. This is a template we may very well see Google put to use today, as it considers whether to release the VP8 codec it acquired in the purchase of On2 Technologies, under an open source or royalty-free license.

In a later slide from the 2006 presentation, Google executives consider the ramifications of three different copyright policy choices for Google Video (GV). One of them is the use of digital rights management technology for premium content. If it had taken that step, the slide suggested, GV's content team would have been tasked with prompting partners including Viacom to make more viral content available, perhaps in shorter streams or promotional clips. Other slides, as well as other documents and presentations from the same period, make it clear Google was aware of partners' concerns that Google was not in the business of promoting content, or featuring or spotlighting some shows for a limited time like a video rental store would...or like YouTube had started doing. But Google was also under the impression (possibly a very correct one) that if it threw away its organic advertising model in favor of a pre-scheduled promotional platform, it would fail to build an audience, and maybe even drive away its existing audience.

So one alternative under consideration was the exact opposite of adding DRM: It considered letting clips happen, if you will. People would upload them, just as they do on YouTube. Under the right circumstances, though, those people could be doing the content owners a favor, especially if GV and those owners had a deal to present those clips anyway.

But content owners tend to decide which clips they don't want visible, after they're already visible. In which case, a slide suggested, in the event of loosening content restrictions for clips, the company could "Support partners' use of review tools," and, "Reach out to non-partner content owners -- actively promote review tool."

Problem is, beyond evangelism, no one could force content owners to use that review tool. So the plan would address that eventuality: "Increase staffing and/or resources to content acquisition, ops, and legal teams to handle complaints and potential litigation," and, "Limit damage through public policy, investor relations, press and premium partner meetings."

The presentation also showed that Google carefully examined the ramifications of building a video system that forced content owners to explicitly "opt out" their own premium clips. In a slide entitled, "Potential results of changing copyright enforcement policies," sure, traffic would improve as users found more and more stuff available, especially those choice "viral" clips. But that influx of users could muddy the waters for Google in determining which specific segments of interesting video could be developed for more refined tastes among small to moderate pockets of GV users. It was here that Google envisioned its real payoff: distinguishing itself from YouTube by providing not viral video, but very interesting video such as documentaries, symposiums, educational works, and stuff small groups of people would pay big money for. In the company's metaphor, where paid premium content such as big movies would be the "head" and user-submitted videos of possums chasing squirrels would be the "tail," this payoff segment was called the "torso." Google reasoned that, if it opened up the floodgates for "tail" content that ended up including bits of "head" content, it would render itself less capable of generating user communities and social networks around "torso" content.

Which, history revealed, was absolutely correct.

In the eventuality of loosening the "tail," Google executives reasoned they would need to mitigate the problem by "Modifying copyright protection through applying public pressure through increased collaboration with content owners and indirect pressure through press and public policy." As a result, the executives predicted, "Some content owners sue Google" (again, very wise). Another potential problem would be certain smarter elements of the press detecting two conflicting messages from the company -- one for loosening copyright for "tail" video content, and another for respecting copyright for all those literary copyright holders whose works were being digitized by Google's ongoing project with the world's major libraries.

The bottom line could be affected, executives reasoned, as the company's AdSense and other platform advertisers "Wish to avoid negative associations." So contrary to Viacom's public assertion that Google was advocating a thwarting of copyright policy to compel content owners to disgorge their clips before a maddening public horde, the evidence actually shows where Google executives logically weighed the negative ramifications of possible public policy changes.

It also shows the beginning of the no-win scenario that eventually led Google to purchase YouTube rather than compete.

Complete documents from the Viacom v. YouTube case are obtainable from this Viacom Web page.