The big change coming to Safari 5: Kernel-level multi-processing

Apple has been challenging Google on many fronts this week -- first with its mobile platform, then with its advertising platform. Earlier today, its developers launched the first volley in the battle's third front, releasing the first public code for the next WebKit rendering and processing kernel that will likely drive the Safari 5 browser.

With Google Chrome using a reworked form of WebKit, the Apple team did something that perhaps any other free and open source developer would be publicly stoned for doing, but which Apple might just have the savvy to get away with: It openly one-upped another developer's open contribution.

"WebKit2 is designed from the ground up to support a split process model, where the Web content (JavaScript, HTML, layout, etc) lives in a separate process," wrote Apple developer Anders Carlsson to WebKit's public mailing list yesterday. "This model is similar to what Google Chrome offers, with the major difference being that we have built the process split model directly into the framework, allowing other clients to use it."

The "process split" model to which Carlsson refers is the architecture that enables processes spawned by the browser, including add-ons and Web apps, to be run as separate processes in the operating system while still being protected by the browser's "sandbox." Google's Chromium team developed the first such model in working form for its Chrome browser.

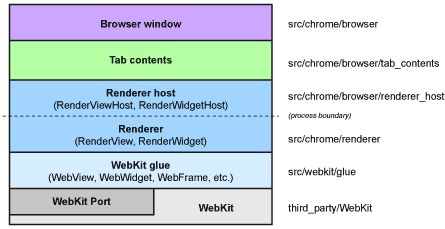

But it was the Chromium team that tried one-upping Apple first, by extracting just the WebKit rendering engine from its open source project files, and replacing its JavaScript interpreter with V8. That may have been a smart move from a performance standpoint at the time. However, in implementing its innovative multi-process model, the Chromium team split the rendering code into two components: a single process host, and a multi-process-capable agent. The two components were designed to communicate with one another via proxy, as Chromium's developers first explained: The renderer and rendering host jointly comprise, they said, "Chromium's 'multi-process embedding layer. It proxies notifications and commands across the process boundary. You could imagine other multi-process browsers using this layer, and it should have dependencies on other browser services."

We could imagine it, certainly; but sharing open source concepts often comprises doing something more than merely imagining. The WebKit team that originated the components that Chromium split into parts, have imagined something different: They foresee moving the user interface components into the multi-process realm, and then enabling APIs from other applications to communicate with those forked processes individually. That way, conceivably, a new single kernel can drive multiple browser tabs whose processes reside on different CPU cores.

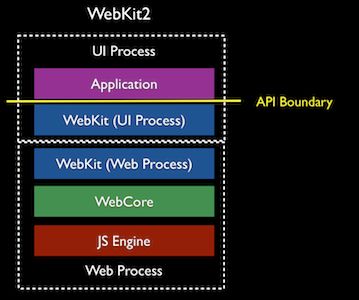

"Notice that there is now a process boundary, and it sits below the API boundary," reads a document published by Apple's WebKit team yesterday. "Part of WebKit operates in the UI process, where the application logic also lives. The rest of WebKit, along with WebCore and the JS engine, lives in the Web process. The Web process is isolated from the UI process. This can deliver benefits in responsiveness, robustness, security (through the potential to sandbox the web process) and better use of multicore CPUs. There is a straightforward API that takes care of all the process management details for you."

"Notice that there is now a process boundary, and it sits below the API boundary," reads a document published by Apple's WebKit team yesterday. "Part of WebKit operates in the UI process, where the application logic also lives. The rest of WebKit, along with WebCore and the JS engine, lives in the Web process. The Web process is isolated from the UI process. This can deliver benefits in responsiveness, robustness, security (through the potential to sandbox the web process) and better use of multicore CPUs. There is a straightforward API that takes care of all the process management details for you."

Unlike Chrome and the Chromium team's work, the WebKit team goes on, they have a responsibility to provide a framework for others to explore and use for their purposes. So if they do a multi-process framework, then it must be in such a way that other developers (even including Google) could facilitate it. However, the facilitators themselves have no such responsibilities. WebKit gently chided Google for having developed Chrome under strict secrecy (something I suppose Apple knows nothing about).

"That was an understandable choice for Google -- Chrome was developed as a secret project for many years, and is deeply invested in this approach," reads WebKit's wiki today. "Also, there are not any other significant API clients. There is Google Chrome, and then there is the closely related Chrome Frame. WebKit2 has a different goal: We want process management to be part of what is provided by WebKit itself, so that it is easy for any application to use. We would like chat clients, mail clients, Twitter clients, and all the creative applications that people build with WebKit to be able to take advantage of this technology. We believe this is fundamentally part of what a Web content engine should provide."

That element which distinguishes WebKit's development philosophy from that of Chrome and Chromium (at least in Apple's eyes) may very well draw a new contour around the type of program -- or rather, the type of platform -- that Safari may yet become. Rather than having a tab for Twitter and a tab for Facebook and a tab for iTunes, a future Safari for all platforms (Mac, iPhone, iPad, Windows) could include a kind of "embedded desktop," or Web-top, where independent applications may reside. They might not appear to run under the context of the browser at all, and if you looked inside each of these processes, you might consider them independent too, capable of being accessed independently through API function calls. But a proxy/stub relationship may connect these processes to the WebKit2 core.

That would go a long way towards solving the iPad's single-tasking problem. The new architecture might also provide a kind of extended platform for something else Apple launched this week: its iAd revenue-sharing advertising system. Imagine, if you will, an advertisement that runs out of the context of the browser. It would not even have to run in the context of the Web page; instead, it could be delivered through one of the applications to which the Safari user subscribes. It might not even be something you can block, not through the ordinary means with which Firefox and IE users are already accustomed. It could even be a potential new revenue stream (or, more accurately, a river) for iTunes.

While you're imagining that...we'll be right back.