Nationwide Google Fiber is a lofty 'pipe dream'

Many people considered this company irrelevant and dead years ago. Yet with nearly three million paying Internet service subscribers still, this provider is anything but dried up -- yet. Internet access, among other subscription services, makes up a clear majority of its continuing sales and its greatest chunk of profits as a whole. Subscriber growth peaked off back in 2002, but for this aging Internet heirloom, at this point they will no doubt take what they can get. Who the heck am I referring to?

Don't choke on your coffee, but it's none other than AOL. Namely, their dialup Internet service division. It's hard to believe that in the year 2013 any company has more than a trickle of subscribers left on dial up, but this attests to the sad state of broadband adoption in the United States. Of the estimated 74 percent of Americans who have internet access in their homes (2010 figures), a full 6 percent of those are still on dial-up service. There are a myriad of issues affecting broadband adoption, including things such as lack of access, pricing, reluctance to switch, etc.

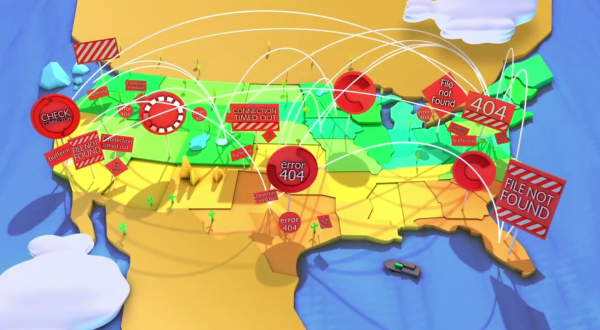

A full 19 million Americans sadly don't have access to any form of broadband. And in a comparison of adoption rate per capita, our country ranks a miserable 15th globally -- behind United Kingdom and South Korea, to name just a few. Much of the Internet is abuzz about Kansas City's recently completed rollout of Google Fiber, with its near gigabit speeds delivered directly to the home.

Even with slow expansion into other small markets, like the recently announced Olathe, KS, the excitement over Google Fiber is premature by all reasonable measures. One giant (Google) is getting into the fiber game while another (Verizon) is slowly exiting after making similar market promises of "fiber to all" just a half decade ago.

While I'm all for nationwide fiber like the rest of us, as an IT consultant by day, I know the tough realities of broadband penetration in our diverse urban & rural mix that is the USA. Here are some of the roadblocks that the pure optimists continue to overlook.

Verizon's Lesson with Fiber: a Messy, Messy Game to be in

Simple economics can explain much of the problem with fast-paced fiber rollout stateside. In many ways, Google could (and should) use Verizon's failed attempt to take FiOS nationwide as a cue to what it can expect in its own forthcoming efforts. It was reported that as of mid last year, FiOS held a nominal subscription base of roughly 5.1 million households. In comparison, the largest cable (coax) broadband provider in the USA, Comcast, holds somewhere between 17-19 million subscribers right now. No wonder Wall Street held Verizon's feet to the fire, and ultimately forced its arm on exiting this 'wild west' of a service buildout.

Most people clamoring for Google to expand Fiber don't know the half of what goes into a fiber network build. Before Google or Verizon can even start taking pre-orders for such service from households, there is a nightmarish mix of legal, financial, and technical boundaries that need to be overcome. Franchise agreements generally have to be negotiated with each and every municipality that is up for consideration. If other providers have exclusivity contracts in a given area, let the legal wrangling begin. And the mess only continues, as a myriad of permits are generally needed to install fresh lines in a small urban area -- including state and local permits, as needed, depending on which roadways and areas are controlled by a given authority.

No better example is needed than the delays that Kansas City, Missouri is running into with rolling out its promised Google Fiber. Local cable providers there are up in arms over Google's preferred treatment by local authorities. More importantly, there is a big rift on how these new fiber lines are to be installed in the community. The preferred, and cheapest, method happens to be utilizing existing cable-ways via electric poles, but this requires using (very) specially trained crews that are quite costly to hire. The current status page for the city shows the first neighborhoods to get service start this month, but that timeline can already be taken with a grain of salt in light of the lack of news on progress there.

Google Fiber promises gigabit speeds at lower prices than even high speed coax cable providers. But is Google the savior to reign in nationwide fiber for all? Possibly, but due to numerous challenges, I doubt it.

The level of paperwork and overhead required in fiber rollout pales in comparison to the cost complexities with actual installations. As seen above, while running fiber on electrical poles is ideal and logical, it is often met with fierce kickback from local municipal higher ups alongside the many others who share these infrastructure pathways -- from electrical companies themselves, to cable providers, and telephone companies, to name a few.

Another option, and one which is less susceptible to weather and the elements, happens to be underground fiber, but this has numerous drawbacks of its own. Digging permits, existing utility lines, and costs related to reconstruction after installation all dog these endeavors to the point where rollout either slows down indefinitely or gets abandoned altogether.

Sprawling suburban areas like my own backyard of Park Ridge, IL provide enough headache for companies like Wide Open West engaging in limited fiber expansion for key areas. I can only imagine what would happen if Google had to install underground fiber in the center of our next-door monster neighbor, Chicago.

Rural America is always an Afterthought

Over 14.5 million Americans, all located in rural areas, still have zero access to any form of broadband. Troubling indeed, and definitely the reason why AOL can still lay claim to nearly three million subscribers. But if you had to pinpoint one reason why broadband penetration in the sticks was so poor, there wouldn't be a single culprit to point fingers at.

Cities and towns blame lack of provider willingness to expand; providers blame staggering costs to build out oodles of infrastructure for a scattering of residents; and rural Americans refuse to pay boatloads for sub-standard broadband when dial up is still relatively dirt cheap. In simple words, the entire situation has been anything but a win-win for any side.

The realities of expanding access in the vast heartland of America is mind boggling. Many small towns sit dozens, if not hundreds, of miles apart from one another and the cabling, manpower, and future upkeep for relatively limited return on investment is what keeps many providers from stretching their reach. The numbers just don't make sense any way they look at it. Even if a small rural town was connected with full fiber access to each neighborhood, the provider would have to outlay nearly all of the capital expenditures necessary to get this in place.

Surely, Google could charge new customers for a fair share of their homes' installation fees, but in order for customers to bite, the price would have to be right. There's no way that Google's fee schedule for Kansas City would hold true for any regular rural community. As opposed to larger urban and suburban centers that take advantage of the economies of scale that come with such locales, rural America would be forced to foot a larger sliver of the installation bill -- or expect Google to do so. If Verizon's FiOS is any lesson for us on fiber rollout, don't expect the latter to hold true in the long term.

While the 2010 initiative under the moniker of the National Broadband Plan was devised to solve these dilemmas, the program has raised more questions then it has solved. Wild cost estimates have still to be hammered out (with some guesses putting such expansion at close to $350 billion USD) and numerous voices of opposition are claiming the NBP will only stifle innovation, growth, and ultimately lead to higher prices for rural areas. A federally backed plan to address broadband is definitely desirable, but in its current form, the NBP is not living up to expectations.

The Chicken or the Egg Dilemma: Subscribers or Penetration First?

This is probably the trickiest aspect to any proposed fiber rollout. Does there have to be a minimum number of potential subscribers in a given area before a provider will promise a fiber expansion? Or does the provider take an educated gamble and just build out blindly? The real answer is one buried in a little bit of both angles to this reality.

ISPs (like Google) of course want to have a solid commitment from a given percentage of customers in a community. But most Americans won't jump on the fiber bandwagon without letting the service(s) mature a bit and outgrow their first iteration bugs. This natural hesitation scares the likes of any potential fiber provider, as their success lays directly with pulling in as many first-generation customers as possible to sustain continued service growth.

Verizon's CFO made it pretty clear last year that the company was opting to raise prices in the face of limited adoption by customers. What choice did Verizon have? They have spent admirably since 2005 to get FiOS rolling in numerous markets (primarily situated on or near the East coast) and while they don't have any new plans for fresh expansion, they do have existing market commitments to uphold.

Fiber isn't something you can roll up and change in relatively short order, such as wireless cell networks moving from WiMAX and HSPA+ to LTE, for example. Fiber is a huge up front expense not unlike our crumbling copper telco network -- once it's here, someone needs to support it one way or another, high prices or not. Those who made the early move either bite the higher pricing, or switch off to older technologies they presumably left for the very same reason. Go figure.

Much of the opposition to fiber adoption could indirectly come from regular citizens who have no intention of switching service providers at all. Even in my broadband-plastered suburb of Park Ridge, our company FireLogic still has customers on dial up service who refuse to upgrade. They are under the illusion that "it just works" and they don't need anything better.

In many cases, the service is either on par or cheaper than the lowest tiers of broadband, so the case against dial up becomes even harder for these individuals. The same goes for customers on sub-standard DSL who will not consider faster options like cable. To many, what they have is what they intend to have for the long term. Fiber won't change their minds unless extreme price hikes made moving a necessity. A path of least resistance keeps services like AOL operating for a sizable minority of its subscriber base.

But if raising prices is Verizon's way of battling limited uptake, doesn't this defeat the goal of cheap fiber for the masses? It most definitely does. Subsequently, it further allows market pricing for competitive providers of cable and DSL service to stay artificially high. As if cable monsters like Comcast needed any more reason to keep prices inching upward. Premature "harvesting" of customers, as analysts are calling Verizon's FiOS moves, is not the solution to establish and keep fiber expansion growing nationwide.

No one knows if Google will be forced into similar corners with its Google Fiber service if adoption doesn't meet expected levels. But if so, those clamoring for the search giant to bring its Fiber service nationwide could start to rethink their wishes.

Google Fiber for All? Lofty, but unlikely

In a perfect world, Google Fiber would blanket America. But if the above roadblocks (and Verizon's own troubles in fiber) are any indication, we need to tone down our expectations quite a bit. Even if Google had the motivation and financial backing to take the service across the USA, it would hit major urban markets first and then crawl outwards into the suburbs at a slow, painstaking pace. Our nation's biggest coax providers started their cable buildouts in the 1960s, and today we are still struggling to extend those networks past suburban areas. History tells an obvious lesson -- infrastructure growth in the United States is a tough-as-hell endeavor, and not for the faint of heart.

The most likely scenario for Google Fiber is a staggered introduction into new markets every few years. The biggest cities would act as the incubators, providing subscriber padding to back capital expenditures and to gauge capacity and upkeep needs for the longer term. Suburbs would then receive service capability once their neighboring saturated urban cities were solidly covered, and those out in rural America would likely be left out in the cold indefinitely.

Unless government subsidies make it financially feasible to bring above-ground fiber to these rural areas, I can foresee Google handling these customers just like Verizon is itching towards doing; cutting off fiber expansion at some point and merely pushing high speed cell coverage through some fashion of partnerships with the likes of Sprint, ATT, Verizon or T-Mobile.

So while it's great to stay optimistic about Google's Fiber plans for the rest of America, let's keep our expectations in check. This entire discussion about nationwide fiber is a topic that feels more like a "been there, done that" style debate when it comes to American infrastructure. Everyone wants it, yet no one knows how to both pay for it and keep it sustainable for the long run. Here's hoping that Google can pull off a miracle, but like many, I'll believe it when I see it.

Derrick Wlodarz is an IT Specialist that owns Park Ridge, IL (USA) based technology consulting & service company FireLogic, with over 8+ years of IT experience in the private and public sectors. He holds numerous technical credentials from Microsoft, Google, and CompTIA and specializes in consulting customers on growing hot technologies such as Office 365, Google Apps, cloud hosted VoIP, among others. Derrick is an active member of CompTIA's Subject Matter Expert Technical Advisory Council that shapes the future of CompTIA exams across the world. You can reach him at derrick at wlodarz dot net.

Derrick Wlodarz is an IT Specialist that owns Park Ridge, IL (USA) based technology consulting & service company FireLogic, with over 8+ years of IT experience in the private and public sectors. He holds numerous technical credentials from Microsoft, Google, and CompTIA and specializes in consulting customers on growing hot technologies such as Office 365, Google Apps, cloud hosted VoIP, among others. Derrick is an active member of CompTIA's Subject Matter Expert Technical Advisory Council that shapes the future of CompTIA exams across the world. You can reach him at derrick at wlodarz dot net.