Digital afterlife: A chance to live forever or never rest in peace?

Have you ever thought about what happens after your physical shell expires? What legacy will you leave and what becomes of it with time? We can give our tangible belongings to friends and family. If the work is copyrighted, the protection will usually extend well beyond the author’s lifespan.

The law has, however, yet to catch up with the times as we also share, store and use tons of information online. That encompasses our digital identity, which is often left unattended after death, lingering at the digital graveyard at the mercy of tech giants.

Our digital ashes will be scattered here and there, but for the most part they will find their final resting place in the overgrown and unkempt grounds of social media platforms. We are the first generation witnessing how the problem of digital afterlife is becoming, well, a problem. But we won’t certainly be the last. The increasingly digital lifestyle of today has given rise to a whole new industry -- the death tech industry. It deals with digital wills, digital legacies and very analog grief.

AI is now used as a crutch to help people grapple with the loss of their loved ones. It can breathe life into great-grandpa’s photos, speak in dead grandma’s voice or even allow us to chat with long-dead loved ones if we feed it enough data -- the more, the better.

From chatbots to VR doppelgangers: How AI brings dead people to life

AI technologies have already revolutionized our lives. It was only a question of time when those very same technologies would revolutionize our death. An AI-powered chatbot called HereAfter aims to do just that. It preserves the "life story" of its customers so that their relatives can reconnect with them after their death. First, the app asks a person detailed questions about his/her life, then that data is then fed into the algorithm. Family members can query the "avatar" of the deceased through the app and receive responses in that person’s voice.

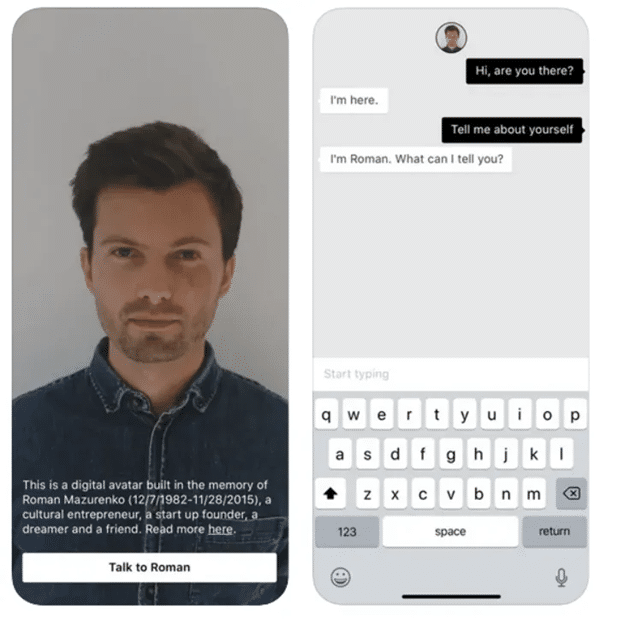

An app called Replica uses deep learning to process human-like text. The more you tell the chatbot, the more it is supposed to become you. Replica was founded by a woman, who lost her friend Roman Mazurenko in an accident. To cope with the grief, she created a chatbot based on that friend’s real text messages by feeding them into an artificial neural network. That chatbot became the predecessor of Replica and is still available for download.

These startups may be fairly obscure, but the technologies they pioneer are here to stay, and sooner or later will be picked up by big tech. In fact, it is already happening. The reason why big companies seem to be dragging their feet on them is not scalability, but ethical and reputational concerns they have to take into account due to their high profile.

Microsoft caused a ruckus last year after patenting a "conversational chatbot" that could be modeled after a specific person who had already passed away. Faced with public backlash, Microsoft quickly backed out from actually building the product.

MyHeritage’s AI-powered DeepStory tool animates portraits of dead people, making them move and speak, though in one of default voices.

As for imitating the voices of real people, Amazon Alexa voice assistant’s new feature promises to enable it.

Some will argue that AI-powered products help families to cope with grief, while others will say that they exploit people when they are at their most vulnerable. AI-powered tech mimicking real people is a double-edged sword, and here’s why.

Fakes, frauds and holograms

The very same tools that help relatives to "reconnect" with their loved ones pose security risks and can be abused to profit off a dead or a living person’s likeness.

The technology has given rise to what is sometimes referred to as "musical necrophilia" or controversial performances by dead artists’ holograms. And last year, a heated public debate broke out after a famed filmmaker "recreated" the voice of late celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain for a documentary.

While such uses of AI are morally and legally questionable, they are up for debate. The more dangerous phenomenon rapidly gaining traction is deep fakes created with an intent to defraud. One of the first widely reported deep fake attacks took place in 2019, when AI-based software was used to mimic the voice of an executive who "directed" his colleague to transfer $243,000 to the fraudster’s account.

The scariest and at the same time the most exciting thing about that technology is that we only witness it taking its first baby steps. Perhaps, one day the living and the dead would be freely meeting in a metaverse. And while metaverses by Microsoft and Meta bet on connecting living people with each other, a metaverse called Somnium Space promises to soon allow relatives to communicate with dead people’s avatars long after they die (provided the deceased themselves had shared with the metaverse enough data in advance).

Your data is at the mercy of tech giants after you die

We can discuss futuristic concepts, but the fact is that most people probably have never thought about what happens with their digital identity after they die. The existing legal void in that area certainly doesn't help.

GDPR does not apply to the deceased, and only a handful of countries have digital inheritance laws. The French law enables people to give instructions to the platforms about the way they want their data to be used after death and relatives to request the erasure of the data. In Germany a court has granted heirs full access to the social media accounts of the deceased. There is no federal law on post-mortem privacy in the US, but states have passed their own laws allowing fiduciaries to manage some digital property, while restricting access to emails, text messages and social media accounts.

It is estimated that there are more than 30 million dead people on Facebook. And by 2070 the dead on the platform are expected to outnumber the living, Facebook allows a user to request the platform to delete his/her accounts upon death or designate a legacy contact who can either request it to be deleted or take care of the memorial page. In the absence of a designated legacy contact, one has first to prove kinship to the deceased or be the executor of the deceased’s estate to make a removal request. If an account is memorialized, it cannot be changed: legacy contact can only update profile and cover photos, write a pinned post, moderate tributes and approve friends requests.

Instagram likewise "memorializes" an account if informed of its owner’s passing. However, only verified next of kin can ask to delete the account and they must prove they have the right to do so under local law.

Twitter offers no memorialization feature despite a promise to create one. The only option for immediate family members if they do not want the account to be open to potential abuse is to request Twitter to delete it permanently.

Google allows users to nominate up to 10 inactive account managers, who can receive various parts of the data linked to the Google account after a certain period of inactivity (3 to 18 months). By default, Google does not provide any content from accounts of deceased users, but may do so "under certain circumstances".

TikTok has neither features for memorialization, nor it allows relatives or representatives to request the deceased user’s account deletion. If an account remains inactive for more than 180 days, the username is reset to a random set of numbers, but the content remains intact.

It’s nice to think that social media behemoths are coming up with such features as memorialization, because they care about their users’ legacy. However, the action might be more profit-driven. Memorialized accounts represent a giant pool of poorly-protected data that tech giants can tap freely into to train their AI applications since no law protects privacy post-mortem. The feature also helps attach still living users to the platform in the long run -- nobody wants to lose access to a loved one’s memorial. That leads to more time spent by the bereaved on social media, and the more time they spend there, the more they are exposed to targeted ads -- the prime source of revenue for Facebook and the like.

Why care?

Getting your digital affairs in order is about sparing your relatives more pain, but also about protecting your digital identity from bad actors post-mortem. Abandoned and seldom-used accounts are easy prey for scammers. Using publicly available information, fraudsters can open digital accounts, access existing accounts, file tax returns and inflict debt on estate representatives. Theft of a digital identity of a dead person has become known as "ghosting."

While heavy bureaucratic machinery is still catching up with the reality of the digital world, the need to take care of one’s digital assets has spawned a new industry, the one that promises to preserve your "digital legacy". A 'death tech' startup GoodTrust says that it will act on behalf of your "digital executor" to memorialize or deactivate social media accounts. MyWishes (formerly DeadSocial) encourages users to create a "social media will" or a log of all social media accounts complete with elaborate instructions what to do with them after you pass away. It goes without saying that by entrusting virtually all your account data to third parties comes with very high risks to your privacy, so it’s only up to you whether to trust these services or not.

What can you do yourself to protect your identity from afterlife abuse?

Death wishes are a matter of personal choice, so what you do with your digital identity is ultimately up to you. Perhaps, you want to live in posterity as a "deadbot" or be recreated as a 3D avatar wandering the metaverse. What we offer is advice that will help protect your name post-mortem and spare your loved ones unnecessary anguish and suffering.

- Do not share anything that you might regret sharing, keep in mind that one day your data may become your legacy

- Protect your social media from digital scavengers that prey on poorly-protected abandoned accounts. Remember that passwords that were considered secure 10 years ago are now easily crackable. Make sure you use a really strong password and have two-factor authentication enabled

- Use existing features offered by social media to safeguard your account: appoint an inactive account manager for Google services, choose a legacy contact for Facebook who can request deletion of your profile after death, etc

- Leave your loved ones clear instructions on how to handle your online identity after your passing. You can do this with the help of third-party services who will act as an intermediary between online platforms and a person you’ll appoint to settle your digital affairs.

- Make a hard and digital copy of all your digital assets, including lists of logins and passwords for all your social media accounts, email accounts, photo sharing sites, utility bill sites and shopping sites and secure them in a law firm’s vault.

- Send your loved ones a letter from the future with a single master key for your password manager like KeePass, who will remember all the passwords for you. This approach, however, only works when you can guesstimate the time of your passing with a high degree of accuracy.

Andrey Meshkov is co-founder and CTO of Adguard.