Another 9/11 anniversary passes quietly

I’ve been quiet lately, I know. My sons’ Kickstarter campaign has taken a toll on their Venture Capitalist… me. I never before appreciated the physical effort that goes into managing what is, for me, a significant investment. They do the work but I pay for a lot of it and that brings with it the need to oversee -- something I’ve never been very good at doing. You’ll see the result, hopefully, next week.

While I’ve been so preoccupied a lot has happened in the technology world. Apple introduced a slew of new products and Alex Gibney released his Steve Jobs documentary. I’ll comment on both of these shortly. Yahoo was denied its tax-free Alibaba spinoff and so has to go to Plan B. I have such a Plan B (or C or D) for Yahoo, myself and will explain it soon. There are some new technologies you ought to know about, too. There are always those.

How I (and you?) am hurting the PC industry

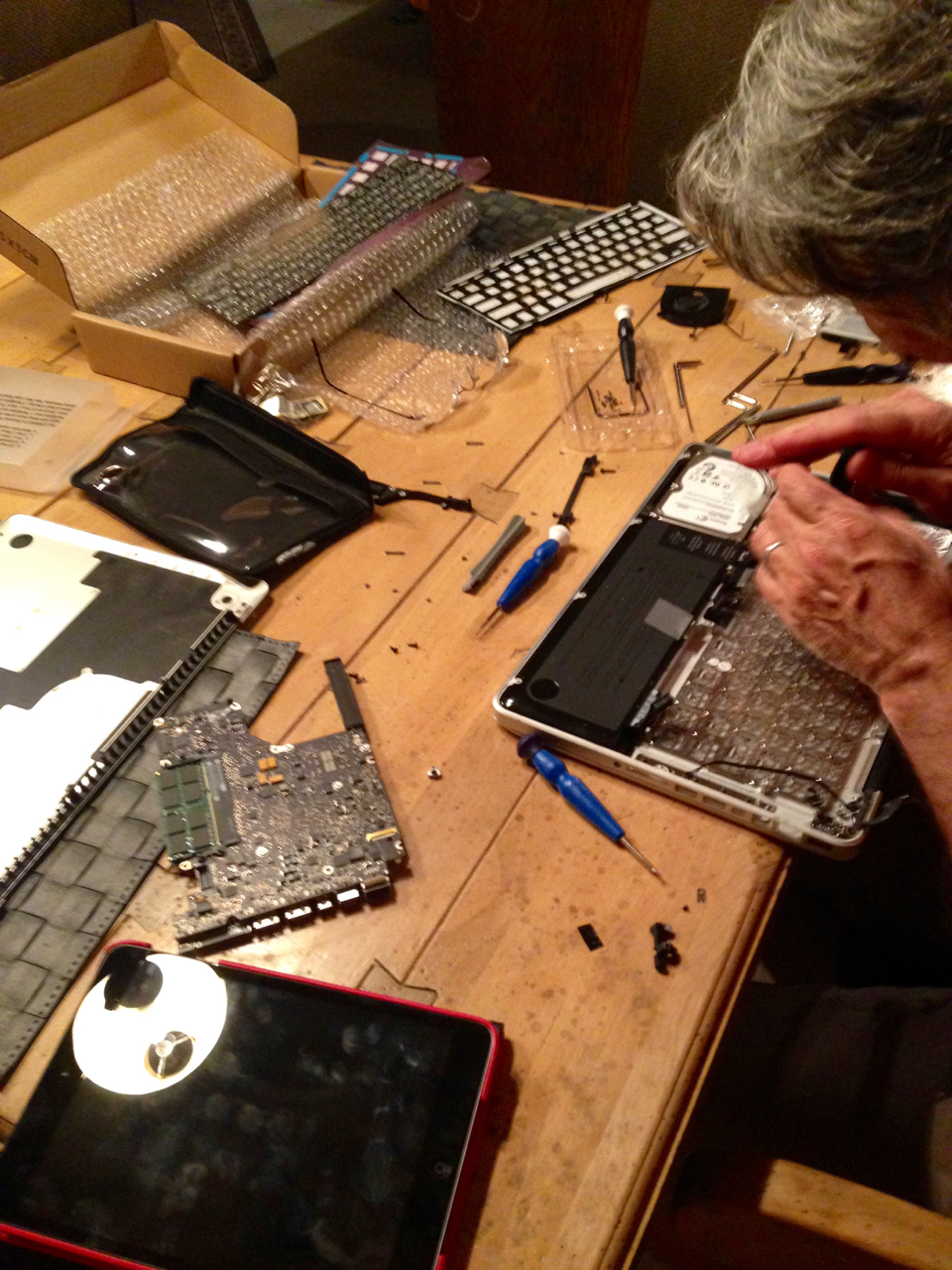

Starting in 1977 I bought a new personal computer every three years. This changed after 2010 when I was 33 years and eleven computers into the trend. That’s when I bought my current machine, a mid-2010 13-inch MacBook Pro. Five years later I have no immediate plans to replace the MacBook Pro and I think that goes a long way to explain why the PC industry is having sales problems.

My rationale for changing computers over the years came down to Moore’s Law. I theorized that if computer performance was going to double every 18 months, I couldn’t afford to be more than one generation behind the state-of-the-art if I wanted to be taken seriously writing about this stuff. That meant buying a new PC every three years. And since you and I have a lot in common and there are millions of people like us, the PC industry thrived.

Who is your IT outsourcing firm working for?

While the US Government has been remarkably opaque about the recently discovered security breach at the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), we know that personal information on at least 21.5 million present, former, and prospective federal employees was lost. The Feds claim Chinese hackers are at the bottom of it, which is disputed by the Chinese government. This, to me, raises a number of questions, especially about the possible role of IT outsourcing firms and implications for organizations beyond OPM. Does IT outsourcing make your data more vulnerable? Yes, I believe it does.

It’s easy to blame the Office of Personnel Management for its own troubles. Oversight was lax. The agency failed a security audit and didn’t seem to do much in response. When shit hit the fan and it became clear that the identity of almost every living person associated in any way with Federal employment had been compromised, the agency lamely offered 18 months of identity theft screening but then didn’t have the money to pay for it. Pathetic. Both the Obama Administration and Congress are to blame, the former for mismanagement and the latter for "starving the beast" by limiting the OPM budget, pushing the agency toward cost-saving decisions that at least to some extent led to the current crisis.

IBM is so screwed

I’ve been working on a big column or two about the Office of Personnel Management hack while at the same time helping my boys with their Kickstarter campaign to be announced in another 10 days, but then IBM had to go yesterday and announce earnings and I just couldn’t help myself. I had to put that announcement in the context you’ll see in the headline above. IBM is so screwed.

Below you’ll see the news spelled-out in red annotations right on IBM’s own slides. The details are mainly there but before you read them I want to make three points.

Remember when technology was exciting?

Al Mandel used to say "the step after ubiquity is invisibility" and man was he right about that. Above you’ll see a chart from the Google Computers and Electronics Index, which shows the ranking of queries using words like "Windows, Apple, HP, Xbox, iPad" -- you get the picture. The actual terms have changed a bit since the index started in 2004 as products and companies have come and gone, but my point here is the general decline.

Just as Al predicted, as technology has become more vital to our lives we’ve paradoxically become less interested, or at least do less reaching out. Maybe this is because technologies become easier to use over time or we have more local knowledge (our kids and co-workers helping us do things we might have had to search on before).

The US computer industry is dying and I'll tell you exactly who is killing it and why

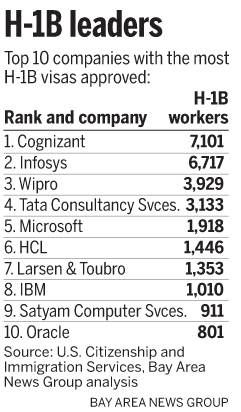

This is my promised third column in a series about the effect of H-1B visa abuse on US technology workers and ultimately on the US economy. This time I want to take a very high-level view of the problem that may not even mention words like "H-1B" or even "immigration", replacing them with stronger Anglo-Saxon terms like "greed" and "indifference".

The truth is that much (but not all) of the American technology industry is being led by what my late mother would have called "assholes". And those assholes are needlessly destroying the very industry that made them rich. It started in the 1970s when a couple of obscure academics created a creaky logical structure for turning corporate executives from managers to rock stars, all in the name of "maximizing shareholder value".

The H-1B visa program is a scam

This is the second of three columns relating to the recent story of Disney replacing 250 IT workers with foreign workers holding H-1B visas. Over the years I have written many columns about outsourcing (here) and the H-1B visa program in particular (here). Not wanting to just cover again that old material, this column looks at an important misconception that underlies the whole H-1B problem, then gives the unique view of a longtime reader of this column who has H-1B program experience.

First the misconception as laid out in a blog post shared with me by a reader. This blogger maintains that we wouldn’t be so bound to H-1Bs if we had better technical training programs in our schools. This is a popular theme with every recent Presidential administration and, while not explicitly incorrect, it isn’t implicitly correct, either. Schools can always be better but better schools aren’t necessarily limiting U.S. technical employment.

Disney's IT troubles go beyond H-1Bs

Disney has been in the news recently for firing its Orlando-based IT staff, replacing them with H-1B workers primarily from India, and making severance payments to those displaced workers dependent on the outgoing workers training their foreign replacements. I regret not jumping on this story earlier because I heard about it back in March, but an IT friend in Orlando (not from Disney) said it was old news so I didn’t follow-up. Well now I am following with what will eventually be three columns not just about this particular event but what it says about the US computer industry, which is not good.

First we need some context for this Disney event -- context that has not been provided in any of the accounts I have read so far. What we’re observing is a multi-step process.

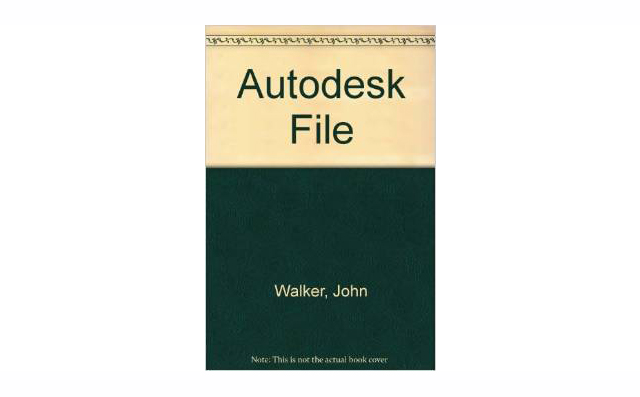

Autodesk's John Walker explained HP and IBM in 1991

One reader of this column in particular has been urging me to abandon for a moment my obsession with IBM and look, instead, at his employer -- Hewlett Packard. HP, he tells me, suffers from all the same problems as IBM while lacking IBM’s depth and resources. And he’s correct: HP is a shadow of its former self and probably doomed if it continues to follow its current course. I’ve explained some of this before in an earlier column, and another, and another you might want to re-read. More of HP’s problems are covered in a very fine presentation you can read here. Were I to follow a familiar path at this point I’d be laying out a long list of HP mistakes. And while I may well do exactly that later in the week, right here and now I am inspired to do what they call in the movies "cutting to the chase", which in this case means pushing through bad tactics to find a good strategy. I want to lay out in a structural sense what’s really happening at both HP and IBM (and at a lot of other companies, too) so we can understand how to fix them, if indeed they can be fixed at all.

So I’ll turn to the works of Autodesk founder John Walker, specifically his Final Days of Autodesk memo, also called Information Letter 14, written in 1991. You can find this 30-page memo and a whole lot more at Walker’s web site. He has for most of this century lived in Switzerland where the server resides in a fortress today. We may even hear from Walker, himself, if word gets back that I’ve too brazenly stolen his ideas. Having never met the man, I’d like that.

Apple TV's 4K Future

On June 8th at the Apple World Wide Developer Conference (WWDC), CEO Tim Cook will reportedly introduce a new and improved Apple TV. For those who live under rocks this doesn’t mean a television made by Apple but rather a new version of the Apple TV set top box that 25 million people have bought to download and stream video from the Internet. But this new Apple TV -- the first Apple TV hardware update in three years -- will not, we’re told, support 3840-by-2160 UHD (popularly called 4K) video and will be limited to plain old 1920-by-1080 HD. Can this be true? Well, yes and no. The new Apple TV will be 4K capable, but not 4K enabled. This distinction is critical to understanding what’s really happening with Apple and television.

First we need to understand Apple’s big number problem. This is a problem faced by many segment-leading companies as they become enormous and rich. The bigger these companies get the harder it is to find new business categories worth entering. Most companies, as they enter new market segments with new products, hope those products come to represent at least five percent of their company’s gross revenue over time. The iPhone, for example, now drives more than 60 percent of Apple’s revenue. Well the Apple TV has been around now for a decade and has yet to approach that five percent threshold, which is why they’ve referred to the Apple TV since its beginning as a hobby.

Sadie's Apple Watch arrived two weeks early

This is Sadie the Dog wearing her new Apple Watch. The watch actually belongs to my young and lovely wife, Mary Alyce, but she was unwilling to be photographed this morning while Sadie will pose anytime, anywhere. This is the Sport model of the Apple Watch in space gray with a black band. What makes this picture interesting is the watch was delivered last Friday two weeks early.

I ordered the watch on the first day Apple was taking orders but didn’t do so in the middle of the night so I missed the first batch of watches that were delivered in April. It was promised for delivery June first. Since then there have been stories about faulty sensors and other suggestions that watch deliveries might be later than expected -- stories that I’d say are belied by this early delivery.

The Kickstarter paradox

Among the great business innovations of the Internet era are Kickstarter and the many similar crowdfunding sites like IndieGoGo. You know how these work: someone wants to introduce a new gizmo or make a film but can only do so if you and I pay in advance with our only rewards being a possible discount on the gizmo or DVD. Oh, and a t-shirt. Never before was there a way to get people -- sometimes thousands of people -- to pay for stuff not only before it was built but often before the inventors even knew how to build it. From the Pebble smart watch to Veronica Mars, crowdfunding success stories are legion and crowdfunding failures quickly forgotten. I’ve been thinking a lot about crowdfunding because my boys are talking about doing a campaign this summer and I have even considered doing one myself. But it’s hardly a no-brainer, because a failed campaign can ruin your day and damage your career.

From the outside looking-in a typical Kickstarter or IndieGoGo campaign is based on the creator (in this case someone like me, not God) having a good idea but no money. If the campaign is successful this creator not only gets money to do his or her project, they get validation that there’s actually a market -- that it’s a business worth doing. About 80 percent of crowdfunding campaigns come about this way.

Your PBX has been hacked!

This past week a very large corporation on the east coast was hacked in what seems to naive old me to be a new way -- through its corporate phone system. Then one night during the same week I got a call from my bank saying my account had been compromised and to press #4 to talk to its security department. My account was fine: it was a telephone-based phishing expedition. Our phone network has been compromised, folks, and nobody with a phone is safe.

Edward Snowden was right we’re not secure, though this time I don’t think the National Security Agency is involved.

AWS shows cloud is NOT a high-margin business

Last week Amazon.com was the first of the large cloud service companies other than Rackspace to finally break out revenue and expenses for its cloud operation. The market was cheered by news that Amazon Web Services (AWS) last quarter made an operating profit of $265 million with an operating profit margin of 19.6 percent. AWS, which many thought was running at break-even or possibly at a loss, turns out to be for Amazon a $5 billion business generating a third of the company’s total profits. That’s good, right? Not if it establishes a benchmark for typical-to-good cloud service provider performance. In fact it suggests that some companies -- IBM especially -- are going to have a very difficult time finding success in the cloud.

First let’s look at the Amazon numbers and define a couple terms. The company announced total AWS sales, operating profit, and operating profit margins for the last four quarters. Sales are, well, sales, while operating profit is supposed to be sales minus all expenses except interest and taxes (called EBIT -- Earnings Before Interest and Taxes). Amazon does pay interest on debt, though it pays very little in taxes. Since tax rates, especially, vary a lot from country to country, EBIT is used to help normalize operating results for comparing one multinational business with another.

Where the money is… or was

Yesterday was Tax Day in the United States, when we file our federal income tax returns. This has been an odd tax season in America for reasons that aren’t at all clear, but I am developing a theory that cybersecurity failures may shortly bring certain aspects of the U.S. economy to its knees.

I have been writing about data security and hacking and malware and identity theft since the late 1990s. It is a raft of problems that taken together amount to tens of billions of dollars each year in lost funds, defensive IT spending, and law enforcement expenditures. Now with a 2014 U.S. Gross Domestic Product of $17.42 trillion, a few tens of billions are an annoyance at most. Say the total hit is $50 billion per year, well that’s just under three tenths of one percent. If the hit is $100 billion that’s still under one percent. These kinds of numbers are why we tolerate such crimes.