Xerox Reignites Interest in Semantic Networking as a Search Tool

The Associated Press this morning hailed a new Xerox innovation that aims to take search engine indexing capabilities "to the next level," with a public unveiling of a semantic networking tool it plans to integrate into its FactSpotter legal document search system. It's being described as the next stage in textual indexing development, and the culmination of a four-year project at Xerox's European research center in Grenoble, France.

But semantic networking has not only been the "next level" of indexing for longer than four years, it's been a factor in indexing since long before the inception of the World-Wide Web. In fact, it was a natural outgrowth of research into hypertext that led to the Web's very creation.

The application Xerox is working to make easier involves legal fact finding, which is a nicer term for what prosecutors refer to as "discovery." When major companies like Intel become subjects of an antitrust investigation, years are literally spent poring through documents, e-mails, brochures, things written on napkins that were somehow saved, in search of evidence that defendants assert they'll be able to find in due course.

A semantic networking tool would expedite that process substantially. Rather than searching for patterns of characters, it understands the contexts in which terms relate to one another, and can locate more relevant information based on words or even discussions and discourses that appear to mean the same thing as the subject of its user's query.

Google's search engine already applies limited forms of contextual pairing, though the Xerox approach could go much further. "Our advanced search engine goes beyond today's typical 'keyword' search or current data-mining programs," stated Xerox Europe researcher Frederique Segond today, "which typically end up searching only 40% of all the documents that are relevant because the keywords are too limiting. Xerox's tool is more accurate because it delves into documents, extracting the concepts and the relationships among them. By 'understanding' the context, it returns the right information to the searcher, and it even highlights the exact location of the answer within the document."

If that doesn't really sound new to you, then you're not dreaming. It certainly wasn't new to me, as I've been a researcher into this very topic since 1992.

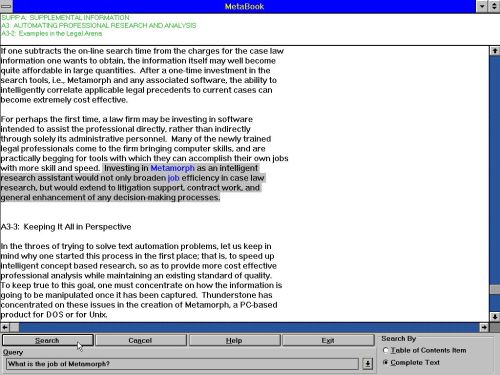

For a 1993 book I wrote for what was then Macmillan Computer Publishing, I interviewed Bart Richards, at that time the CEO and founder of a company called Thunderstone, which had then produced a semantic network indexing tool called Metamorph. Since that time, Metamorph was integrated into a product called Texis - the first SQL engine to understand both relational and semantic logic. A modern version is in use today, powering many of the Web's prominent online catalogs.

Richards has since retired, though his explanation of Metamorph from nearly 14 years ago could essentially apply to exactly the concept Xerox's Segond introduced to legal industry customers this morning:

For Metamorph to be effective...it cannot limit itself to just the meanings two near or adjacent words have that are similar to one another, as Thunderstone's Bart Richards explains in demonstrating how a Metamorph query works: "The Metamorph query is searching for some kind of set logic, some satisfaction of sets in some communication unit. Two [such] sets would be bear and arms within a sentence. The communication unit is the sentence, and bear and arms are the things that we're looking for. The key tool of linguistic computing is the parser, a device which interprets sentence structure. Its design predates the advent of graphical computing, and its underlying principles are nearly 40 years old.

"The way the query is implemented is as follows: The user types the query in one of a number of different ways; he can use logic or natural language. It depends on how sophisticated the user is. By default, [Metamorph] takes the words or phrases that it locates on the query line, and expands them into their sets. Suppose you say, 'What is my right to keep and bear arms?' What Metamorph would do is break that down into four sets: right, keep, arms and bear, which are very interesting little beasties, because both of them have quite a few meanings. There's four main meanings for each of those words. We would expand each one of those words to the set of things that means each of them."

Bart Richards goes on to state that Metamorph does not apply precise meanings to any one word in its vocabulary table. Instead, he tells us, "it's in conjunction with one another that [the words in the table] carry their meaning. Their meanings are obtained from the words around them, the words that precede them. There's implicit communication that happens in in-context meanings. If you say, 'bear' by itself, you have no clue what it means; but as soon as you say 'arms,' you know exactly what it means. But if you take 'bear' and 'woods,' the thing that lights up in your head is a brown, fuzzy kind of bear. So what the software is trying to do is reduce to the lowest common denominator the ideas that are communicated in the text, and the ideas that you are communicating on the command line."

Many of the terms Metamorph has catalogued are not individual words; some of them are idiomatic word pairs. Bear arms is not really an example, since arms doesn't serve to change the meaning of the word bear. Give up is an example, since the act of giving up has little or nothing to do with give, nor much of anything with up. Bart Richards: "We automatically do things like phrases and idiomatics. It'll recognize 'state-of-the-art' as a phrase, but it won't expand it out to the meanings unless I ask it to. If you ask, 'What is the state-of-the-art in high-tech electronics?' we'll know what you meant by that query. We recognize 'high-tech' as one thing, not 'altitudinal technology.'"

For the record, Xerox has been involved in semantic networking theory and research for far longer than four years, though its public presence in that field might make it seem as though it had only been around for that short a time.

|

| A demonstration program showing Metamorph's capability to automatically find contextual links in ordinary text, and highlight those as hyperlinks. Yes, that's Windows 3.1 it's running on, because this demo took place in 1993. Notice the subject of the text being searched: It talks about Metamorph's possible applications for the legal industry. |