'Open Access' Wireless Auction Could Be All for Naught

Tuesday's 4-1 vote by the US Federal Communications Commission begins a process whereby a portion of the UHF television spectrum - specifically, between 775 and 793 MHz, in the midst of what we now call Channels 64 through 67 - would be auctioned off only to companies willing to keep a promise: To allow customers of wireless services they deploy on that spectrum to use the devices of their choice, rather than the ones the carriers choose for them; they could use any applications they wish on those devices; and they would make their services available to public safety in emergencies.

Google had hoped for a few more concessions on the FCC's part, one being a net neutrality promise not to resell frequencies to select customers at discount rates, the other being a promise to allow smaller companies to purchase access to frequencies at wholesale rates.

Actually, it was former Netscape chairman Jim Barksdale who originally urged the FCC to consider these open access rules for the 700 MHz spectrum auction. But it was Google that commandeered the movement with its promise to bid $4.6 billion for 22 MHz valuable frequencies in the so-called "C-block," if the FCC were to adopt those four recommendations.

Now that the Commission has agreed to implement only a limited subset of those recommendations, it faces a new and not altogether unexpected problem: Based on what it has learned from wireless companies, according to Commissioner Robert McDowell - the lone dissenter - no one may be interested in bidding. Not Google, not AT&T, not Verizon, not Rupert Murdoch, not Bubba's Bait & Tackle.

"Throughout this proceeding, I have not heard a convincing argument refuting why wealthy Silicon Valley new entrants are not as capable of bidding on unencumbered spectrum as other wealthy companies," Comm. McDowell stated Tuesday. (By "encumbered," he's referring to the restrictions the majority of the FCC voted to place on the auction.) "More importantly, I remain unconvinced that the Commission must favor large companies over smaller entrepreneurs. Why not give both an equally fair shot with one free, open, condition-free auction that offers varied market sizes and spectrum blocks?

"Curiously, however, in an effort to favor a specific business plan, the majority has fashioned a highly tailored garment that may fit no one," McDowell continued, with his usual flair for rhetoric. "It's not what Silicon Valley wants, it's not what small players have told me they want, and it's not what rural companies want. To date, the Commission has received no assurances that any company is actually interested in bidding on the encumbered spectrum. Not one. The majority recognizes the risk that the encumbrances pose, yet has taken the unprecedented step of designing a fallback, 'Plan B' auction in the event the first auction fails. Perhaps the majority has only little more confidence in its plan than I do."

What makes the current plan so different than the jackpot Google was looking for, first and foremost, is that bidders are not compelled to make wholesale access available to small blocks of purchased frequency, to other wireless customers.

If Google were still interested, it could place a bid, but it would be against major players like AT&T, Verizon Wireless, and Sprint. At this point, Google is under no restrictions to bid $4.6 billion or higher - it could bid less. But the other players could still conceivably mount a joint bid, creating a voting bloc that could knock out Google the way they knocked out News Corp. in an auction last year, for spectrum Rupert Murdoch wanted to use for DirecTV Internet services.

There's also the fact that it's not, to borrow the old phrase, the same time or the same channel. As the FCC's Wireless Telecommunications Bureau Chief, Fred Campbell, explained on Tuesday, "In order to foster innovation and competition, today's order requires licensees of the largest block of commercial spectrum to provide a platform that is more open to devices and applications. Specifically, licensees in this block must allow consumers, device manufacturers, third-party application developers, and others to use the devices and applications of their choice on a licensee's network, subject to certain conditions. Today's order does not impose broader requirements on licensees, such as wholesale requirements."

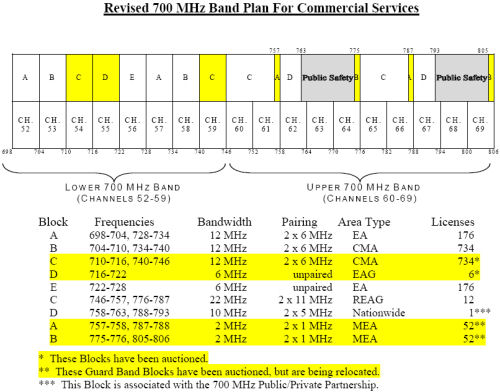

"The order also revises the band plan for the entire 700 MHz band," Campbell continued. "Under the new band plan, 62 MHz of spectrum for commercial use will be made available via auction. This spectrum will be licensed using a diverse mix of geographic areas and spectrum block sizes that facilitate broadband deployment, and to accommodate a wide range of applicants, including small and rural providers.

Referring to the new diagram, Campbell pointed out, "The band plan for commercial services includes one paired 12 MHz block, the lower B-block, to be licensed on a geographic area basis using small, cellular market areas (CMAs) consisting of 734 license areas. In addition, the lower A- and E-blocks - a paired 12 MHz block and an unpaired 6 MHz block, respectively - will be made available in medium-sized economic areas (EAs) consisting of 176 license areas. One paired 22 MHz block - the upper C-block - will be made available in large regional economic area groupings (REAGs), consisting of 12 license areas, and will be subject to the open platform conditions just mentioned."

These blocks are portions of the 700 MHz spectrum that were originally reserved for use by a nationwide public safety emergency communications network. Without sufficient federal funding available for such a network (the war having usurped available moneys for public safety and other luxuries), organizers of the national public safety network decided to raise money for its own purposes by auctioning off portions of the reserved spectrum that it was unlikely to use for itself.

The way the current band plan slices and dices the spectrum, only the C-block would probably be of interest to a potential bidder whose business plan would be to resell portions of that block to smaller, competitive wireless services. Google may still be one, but that likelihood was extremely diminished - if not extinguished - on Tuesday.

Next: Can the FCC avoid “Plan B?”