5 things you should know about Apple iCloud

I'm having freaky sense of déjà vu, today. Apple may be late to cloud computing, but what's that saying about better late than never? Late has worked for Apple before, and I expect it to do so again.

Apple was late to music, when it launched iTunes in January 2001. The Napster revolution was well underway and Windows PC manufacturers shipped CD-RW drives. Now look at Apple and music. Apple was late to smartphones and tablets. Now it has shipped 200 million iOS devices, 25 million of them iPads -- in just 14 months. The list is longer, but you get the point.

Now Apple is late to the cloud, and, whoa, what timing. Apple's forthcoming iCloud fundamentally is different from services of seemingly similar ilk. Earlier today at Worldwide Developer Conference, CEO Steve Jobs unveiled the service, which is available to Apple developers now and to the general public in the Fall.

Some Mac fans will argue that Apple isn't late at all, because of MobileMe. But it rightly felt like an incomplete service, particularly compared to what Google offers. Apple is catching up to Google and passing it, by fundamentally changing how cloud services are generally deployed. With that introduction, I offer 5 things you should know about iCloud presented in no order of importance.

1. iCloud is more push than pull. Most cloud computing services pull content up rather than push it down or around. This is how Google does it. Users store email in the cloud or upload music for streaming back to devices. Ditto for photos. Google Apps documents are created in the cloud and only leave if exported by the user.

The difference is this: Most existing cloud services require manual processes for uploading or downloading content. iCloud does most of this work automatically, and it's designed to push content to devices rather than hold it in the cloud (see #2).

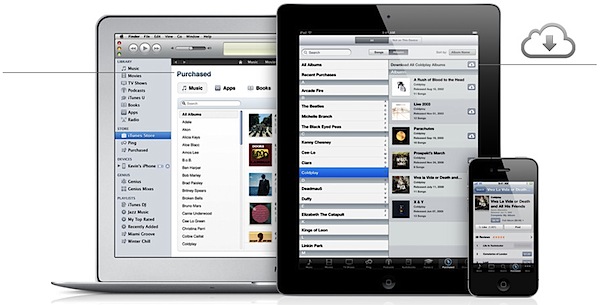

2. iCloud fundamentally is a synchronization service. To many people used to services like Dropbox, or even Windows Live SkyDrive, iCloud will likely look like an online storage service. It's not -- even though such capability is available. Storage is there to facilitate sync across multiple devices -- Macs, Windows PCs, smartphones, music players and tablets. Other services primarily sync to the cloud, while Apple's service uses the cloud to sync content among devices.

In 2006, I started writing about the importance of synchronization and it being a killer application. My March 2008 Microsoft Watch post "Do IT simply with sync" best captures my thinking about the importance of sync: "Synchronization is the natural killer application for the connected world. People use multiple devices, software products and IP/Web services. Information spreads out across these devices, requiring unnecessary rekeying and duplication. Synchronization would solve these problems and make content more useful across devices or services."

Apple has taken a better approach to sync by focusing on its fundamental benefit to users: Simplicity. It's also unsurprising that Apple would take a sync-across devices approach. After all, the company generates most of its revenue from selling hardware, not offering cloud services.

iCloud can sync calendars, contacts, documents, email, photos and even music (see #4), among other content categories.

3. iCloud replaces iTunes as Apple's main synchronization hub. This perhaps is the most significant function, from a strategic perspective. Sync was iTunes' killer feature from release of the first iPod in October 2001. Over time, iTunes became Apple's major sync hub, but it was the wrong place -- particularly for corporations looking to manage iPads and iPhones. Apple's music player has been an antiquated, legacy synchronization hub for far too long, particularly with Google offering great cloud sync to Android devices.

iCloud replaces iTunes necessity and extends beyond its capabilities by, for example, syncing more content types. Even apps and music (see #4) are synced from the cloud -- no iTunes required as sync hub.

4. iCloud is not a music streaming service. There are reasons why I rarely post rumors; they often tend to be wrong -- as was the majority asserting iCloud would offer music streaming. It does not. The iTunes portion is for content syncing.

The first hard rumors -- stupid speculation, really -- started in December 2009, when Apple bought music streaming service Lala. I wrote then: "I don't see streaming as a viable music business model for Apple; there's more revenue to lose than to gain." However, I could see Apple using Lala technology for improving music discovery by increasing song sampling. Apple later did just that, going to 90-second song samples from 30 seconds. With more wild rumors circulating, I later emphasized: "Streaming doesn't make sense, particularly when Apple has done so well with content people own."

But the music rumormongers expected just that -- a service like Amazon's or Google's for streaming content people already own. Amazon launched its Cloud Player and Cloud Drive services in late March. Google Music is in beta. What Apple has done is so much better. Keeping to the push principle, iCloud provides the content to the user for downloading and syncing among devices. Amazon and Google music service users must upload their libraries. From Apple it's push down in a big way. Hey, Apple already knows what music you purchased from iTunes.

5. MobileMe is now free. Apple had charged $99 a year for the service -- more for the five-member Family Pack. With iCloud, MobileMe is free, and there is 5GB storage available. But Apple doesn't count purchased apps, ebooks or music and photos against the storage capacity. Why? As I stated earlier, iCloud is not a storage service -- it's about sync.

The MobileMe portion will be advertising-free, which is highly unusual for cloud services these days.

I presume that Apple will charge for storage above 5GB, then there is the $24.99 yearly fee iTunes Match. For music that people didn't buy from Apple, the service scans their computers and checks against the iTunes' 18 billion song catalog. These songs are added to the library and made available for sync or download -- in 256kbps AAC. Again, it's push. The user doesn't have to upload anything.