This is how Facebook tracks you

On September 25, Nik Cubrilovic posted a terrific analysis looking at how Facebook uses cookies to track users even when they have signed out of the service. His findings about Facebook cookie tracking raises yet more red flags about subscriber privacy. We asked and he granted permission to repost the analysis, which differs in two subtle ways from the original: Slight editing for house style and incorporation of two updates into the main text. We also changed the headline.

Dave Winer wrote a timely piece yesterday morning about how Facebook is scaring him since the new API allows applications to post status items to your Facebook timeline without a user's intervention. It is an extension of Facebook Instant and they call it frictionless sharing. The privacy concern here is that because you no longer have to explicitly opt-in to share an item, you may accidentally share a page or an event that you did not intend others to see.

The advice is to log out of Facebook. But logging out of Facebook only de-authorizes your browser from the web application, a number of cookies (including your account number) are still sent along to all requests to facebook.com.

Even if you are logged out, Facebook still knows and can track every page you visit.

The only solution is to delete every Facebook cookie in your browser, or to use a separate browser for Facebook interactions.

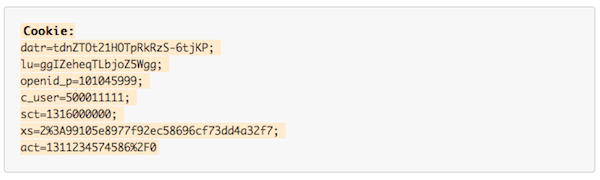

Here is what is happening, as viewed by the HTTP headers on requests to facebook.com. First, a normal request to the web interface as a logged-in user sends the following cookies:

Note: I have both fudged the values of each cookie and added line wraps for legibility.

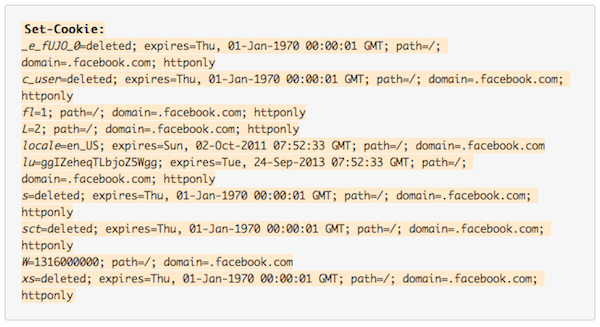

The request to the logout function will then see this response from the server, which is attempting to unset the following cookies:

To make it easier to see the cookies being unset, the names are in italics. If you compare the cookies that have been set in a logged-in request, and compare them to the cookies that are being unset in the log-out request, you will quickly see that there are a number of cookies that are not being deleted, and there are two cookies (locale and lu) that are only being given new expiry dates, and three new cookies (W, fl, L) being set.

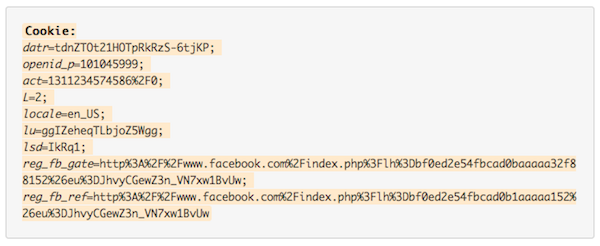

Now I make a subsequent request to facebook.com as a 'logged out' user:

The primary cookies that identify me as a user are still there (act is my account number), even though I am looking at a logged-out page. Logged-out requests still send nine different cookies, including the most important cookies that identify you as a user

This is not what 'logout' is supposed to mean. Facebook are only altering the state of the cookies instead of removing all of them when a user logs out.

With my browser logged out of Facebook, whenever I visit any page with a Facebook Like button, or Share button, or any other widget, the information, including my account ID, is still being sent to Facebook. The only solution to Facebook not knowing who you are is to delete all Facebook cookies.

You can test this for yourself using any browser with developer tools installed. It is all hidden in plain sight.

If you wish to view the raw logs, I have saved them here. Specifically the datr and lu cookies are retained after logout and on subsequent requests, and the a_user cookie, which contains your userid, is only cleared once the session is restarted. Most importantly, connection state is retained through these HTTP connections. There is never a clean break between a logged in session and a logged out session.

An Experiment

This brings me back to a story that I have yet to tell. A year ago I was screwing around with multiple Facebook accounts as part of some development work. I created a number of fake Facebook accounts after logging out of my browser. After using the fake accounts for some time, I found that they were suggesting my real account to me as a friend. Somehow Facebook knew that we were all coming from the same browser, even though I had logged out.

There are serious implications if you are using Facebook from a public terminal. If you login on a public terminal and then hit 'logout', you are still leaving behind fingerprints of having been logged in. As far as I can tell, these fingerprints remain (in the form of cookies) until somebody explicitly deletes all the Facebook cookies for that browser. Associating an account ID with a real name is easy -- as the same ID is used to identify your profile.

Facebook knows every account that has accessed Facebook from every browser and is using that information to suggest friends to you. The strength of the 'same machine' value in the algorithm that works out friends to suggest may be low, but it still happens. This is also easy to test and verify.

I reported this issue to Facebook in a detailed email and got the bounce around. I emailed somebody I knew at the company and forwarded the request to them. I never got a response. The entire process was so flaky and frustrating that I haven't bothered sending them two XSS holes that I have also found in the past year. They really need to get their shit together on reporting privacy issues; I am sure they take security issues a lot more seriously.

To clarify, I first emailed this issue to Facebook on the 14th of November 2010. I also copied the email to their press address to get an official response on it. I never got any response. I sent another email to Facebook, press and copied it to somebody I know at Facebook on the 12th of January 2011. Again, I got no response. I have copies of all the emails, the subject lines were very clear in terms of the importance of this issue.

I have been sitting on this for almost a year now. The renewed discussion about Facebook and privacy this weekend prompted me to write this post.

The Rise of Privacy Awareness

Ten to 15 years ago when I first got into the security industry the awareness of security issues amongst users, developers and systems administrators was low. Microsoft Windows and Internet Information Server were swiss cheese in terms of security vulnerabilities. You could manually send malformed payloads to IIS 4.0 and have it crash with a stack or heap overflow, which would usually lead to a remote vulnerability.

A decade ago, the entire software industry went through a reformation on awareness of security principles in administration and development. Microsoft re-trained all of their developers on buffer overflows, string formatting bugs, off-by-one bugs etc. and audited their entire code base. A number of high-profile security incidents raised awareness, and today vendors have proper security procedures, from reporting new bugs to hotfixes and secure programming principles (this wasn't just a Microsoft issue, but I had the most experience with them).

Privacy today feels like what security did 10-15 years ago. There is an awareness of the issues steadily building, and blog posts from prominent technologists is helping to steamroll public consciousness. The risks around privacy today are just as serious as security leaks were then -- except that there is an order of magnitude more users online and a lot more private data being shared on the web.

Facebook are front-and-center in the new privacy debate just as Microsoft were with security issues a decade ago. The question is what it will take for Facebook to address privacy issues and to give their users the tools required to manage their privacy and to implement clear policies - not pages and pages of confusing legal documentation, and 'logout' not really meaning 'logout'.

Erratum: I refer to the wrong cookie name in the post above. I also say 'all sites' can be tracked, when I meant to say 'all sites that integrate facebook'.

Nik Cubrilovic is an Australian-born serial entrepreneur, writer and hacker. He currently is working on pre-launch startups, previously at Techcrunch, Omnidrive and a number of other startups since 2000. He has lived in Australia, Bosnia, the UK, South Africa and the USA; Cubrilovic is currently based in Wollongong, Australia.

Nik Cubrilovic is an Australian-born serial entrepreneur, writer and hacker. He currently is working on pre-launch startups, previously at Techcrunch, Omnidrive and a number of other startups since 2000. He has lived in Australia, Bosnia, the UK, South Africa and the USA; Cubrilovic is currently based in Wollongong, Australia.