Mars Rover Curiosity camera isn't as good as your cell phone's

NASA's Curiosity rover landed on the surface of Mars on Sunday night, and almost immediately began transferring back to Earth the first images of the Martian surface. But for its reported $2.5 billion price tag, the images have a little less clarity than you might expect.

Curiosity's cameras have a maximum resolution of two megapixels. For perspective's sake, modern smartphones typically are 8MP or more. The result will be images that are sharper than those of Martian rovers past, yet lack the clarity that would be expected of a modern research craft.

So why does Curiosity have such a low-tech camera on board? There are two big reasons: the rover's long developmental period and limitations on the transmission of interplanetary data, says camera project manager Mike Ravine of Malin Space Science Systems.

In an interview this week with Digital Photography Review, Ravine notes that his company had been working on Curiosity's cameras as early as 2004. The specifications called for 8GB of on-board flash memory, which may sound like a lot is not much considering the rover's two year mission on the planet's surface.

A two-megapixel camera will obviously produce images that are small enough in size to permit thousands of images to be stored in Curiosity's on-board memory. Additionally in 2004 terms, 2MP wasn't so low-tech as it is now. That's when the design for the camera was proposed, and Ravine notes that his company couldn't develop something else once NASA approved its proposal.

An even bigger consideration for both NASA and Ravine's team is bandwidth. As it stands now, interplanetary data transmission is a slow and tedious process. Curiosity sends data to two satellites currently orbiting Mars -- the former Mars Reconnaissance and Mars Odyssey orbiters -- which then transmit data back to Earth. But at a speed of only 128Kbps, it's still quite slow in modern terms. This is not a lot of bandwidth given the scope of the Curiosity mission.

While pictures are what most of us are going to associate with the Curiosity mission, the rover has far more data that it must send back. With only about 250 megabytes of data able to be transmitted back to Earth daily according to Ravine, bandwidth is at a premium.

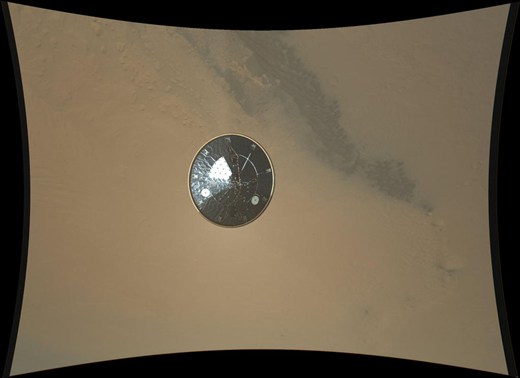

There still should be visually stunning images from these cameras. The image shown below of Curiosity's heat shield falling away from the rover before final descent is arguably one of the clearest images sent back from an outer space research vessel yet. At the same time, these will be the exception and not the rule as NASA will need to pick and choose which images to retrieve due to the lack of bandwidth.

So how do we solve this bandwidth problem? At last year's TEDxMidAtlantic event in Washington, D.C., Google chief evangelist and "Father of the Internet" Vint Cerf talked about the need for an interplanetary Internet. The beginnings of such a system already exists in how NASA and other space agencies are repurposing orbiting spacecraft to become communications relays.

But what happens when spacecraft begin to travel longer distances in their missions, say to distant stars like Alpha Centauri? Our modern point-to-point radio link system will be far less reliable, and the delays will be immense. It will soon be time to re-imagine how our spacecraft "phone home", or face an ever more difficult time in leveraging our modern technologies to advance the pace of space research.