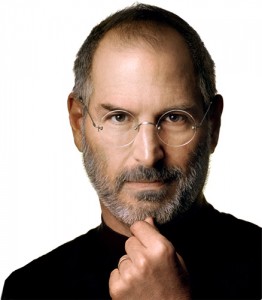

Why we love Steve Jobs

In about six weeks, the InterWebs will flood with posts commemorating a tech visionary's passing. Steve Jobs died on Oct. 5, 2011. A year ago last week, he stepped down as Apple's CEO. Jobs is a colorful, iconic, flawed figure, who stands before us something more than mere mortal. That's because his public life has a literary quality that cuts to the core of our humanity.

In about six weeks, the InterWebs will flood with posts commemorating a tech visionary's passing. Steve Jobs died on Oct. 5, 2011. A year ago last week, he stepped down as Apple's CEO. Jobs is a colorful, iconic, flawed figure, who stands before us something more than mere mortal. That's because his public life has a literary quality that cuts to the core of our humanity.

I got to thinking more about this today following a discussion with colleague Tim Conneally and questions answered for a CNN reporter about Microsoft (apologies to him, I removed those sentences and use them here). I asked Tim today: "Why is Steve Jobs so endearing? Redemption. What's that term in fiction about the hero's journey? Steve Jobs followed the path in real life". There's something Shakespearean, too -- the fatal flaw that humbles greatness. Mixed together, his story should be a great fictional work. But it's better and haunting being real life.

Salvation Story

Redemption is one of the most common fictional themes, and it is pervasive in American cinema. There are so many examples, I hardly can cite them. To name a few: Casablanca, Gladiator, Hoosiers, In the Line of Fire, It's a Wonderful Life, Star Wars I-VI, Tender Mercies, The Dark Night Rises, The Natural and The Verdict. A hero falls from grace and gets a second chance to right past mistakes. This is Jobs' journey, from the founding of Apple to his ouster soon after the tech-transforming Macintosh launches to his exile at NeXT to his return to Apple and the company's rise from rubble to riches.

Apple neared bankruptcy when Jobs returned in late 1996, with the purchase of NeXT. By summer 1997, he stood before the Mac faithful as interim CEO and began the tough task of rebuilding Apple. For example: killing off products and ending the clone program that allowed third parties to build computers running the company's flagship operating system. Then Apple's reinvention started -- in 1998 with iMac's release, which set off a wave of translucent-designed products. In 2000, Jobs introduced the ill-fated G4 Cube, which flopped, leading Apple to overstock inventory, to announce a profit warning and to watch the share price collapse overnight.

But in the midst of adversity, Jobs persevered. The path to redemption isn't easy in fiction, and no less so in real life. In one year, 2001, Apple launched iTunes, Mac OS X and iPod, while also opening its first retail stores. From there followed a nearly continuous line of successful products, culminating in iPad 18 months before Jobs' death.

At critical junctures Jobs and Apple took great risks:

- Launching architecturally-changed Mac OS X months before Windows XP.

- Opening retail stores during a recession and while rival Gateway shuttered hundreds.

- Releasing a MP3 player into a category where Apple had no expertise or design experience.

- Debuting an online music store when CDs ruled the world and record companies resisted the concept.

- Killing off iPod mini at the height of its popularity and replacing it with the diminutive iPod nano.

- Developing and releasing a smartphone, on a single carrier, into a category with entrenched leaders like Nokia.

- Defying pundits (I was one of them) and with iPad moving into the tablet category, where Microsoft, Sony and others had failed.

There are no rewards without risks, and no redemption either. We love our fallen heroes, who succeed at second chances. As such, Jobs' story endears.

Hero's Journey

But Jobs' story is more than the path of the fallen to redemption. His is another literary concept -- the classical hero's journey, or monomyth, as described by Joseph Campbell. The hero follows a fairly well-defined path that in the broadest description has three parts: separation, initiation and return. In modern literature, Harry Potter is perhaps the most well-known example of the hero's journey. He begins life in a magical family, but his parents are killed, leading him to live with aunt and uncle. At 11, Potter learns he is a wizard and follows a path of training, hardship and mistakes that leads him to fulfill his destiny battling and defeating Lord Voldemort. But Potter doesn't act alone, assisted by Hermione Granger, Neville Longbottom and Ron Weasley, for example.

Star Wars is another hero's journey, and yet redemption story, too. Luke Skywalker's parents are killed (or so he's told), leading him to live with aunt and uncle. He is called (and first refuses) to go with Obi-Wan Kenobi to study the ways of the Force. Like Potter, Skywalker walks a path of training, hardship and mistakes (he fights Darth Vader too soon), developing mystical/magical abilities along the way. But Skywalker doesn't act alone, assisted by Princess Lea, Han Solo and the Rebellion, for example.

The redemption story is another's -- the elder Skywalker's fall from being the prophesied "chosen one" to Darth Vader to later repentance and restoration after killing the evil emperor.

There's a real-life Hero's Journey quality to Jobs' life -- raised by adoptive parents, mentored by Steve Wozniak and set out on the journey founding Apple. But after being cast out, Jobs built NeXT and created Pixar (from the graphics company acquired from Lucasfilm). During the journey, and hardship, Jobs developed skills running two companies -- and seemingly magical good sense -- that he brought back to Apple. There Jobs vanquished not one but many adversaries, with Microsoft being the one mattering most to many long-time Mac users. But Jobs didn't act alone, assisted by Tim Cook, Scott Forstall and Jony Ive, for example.

Jobs' tale is more tragic, for obvious reasons, which in some ways makes his journey and legacy all the more endearing (and sad, too).

My point: There's something innately appealing -- and universal -- about the monomyth and redemption stories. Jobs' life imbues qualities of both. Then there is inarguable success. Who cannot stand in awe, denying it? Apple is the world's largest company, as measured by market capitalization -- a rubble to riches story in just 14 years, counting from when Jobs returned (at first) as interim CEO until he stepped down as chief executive because of ill-health.

Jobs was known for his remarkable, aspirational product announcements and the seemingly magical ability to get people listening charged up to buy, believing perhaps living would be better for it. Jobs' life -- rise, fall and redemption -- is an aspirational story that transcends the best literature and speaks to the desires that make us all human.