The encryption backdoor debate: Why are we still here?

Earlier this month, reports emerged that the UK government had pressured Apple, under the Investigatory Powers Act 2016, to create a backdoor into encrypted iCloud data. Unlike targeted access requests tied to specific cases, this demand sought a blanket ability to access users’ end-to-end encrypted files.

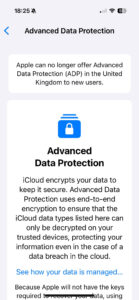

Apple was forced to reconsider its Advanced Data Protection service in the UK, and this latest development raises a fundamental question: Why does the debate over encryption backdoors persist despite decades of technological progress and repeated warnings from cybersecurity experts?

The flawed logic of encryption backdoors

The UK government’s latest demand may be unique in its scope, but it is not without precedent. Governments worldwide have long sought ways to access encrypted communications for national security and law enforcement purposes. We saw this in the FBI’s battle with Apple in 2016 over unlocking a terrorist’s iPhone and more recently with the European Commission’s 2022 “chat control” proposal that attempted to mandate mass scanning of encrypted communications for potential child abuse material.

These efforts are often framed as necessary for public safety and national security. On the surface, this appears reasonable. After all, who wouldn’t want law enforcement authorities to have the tools necessary to catch criminals or would-be terrorists?

But the problem is that encryption backdoors don’t function like a controlled access key that only legitimate authorities can use. Instead, they introduce systemic risks into encryption protocols, making systems more vulnerable to cybercriminals, hostile nation-states and even rogue insiders.

This is not hypothetical fear-mongering. In 2019, the NSA’s EternalBlue exploit -- originally developed as a cybersecurity tool -- was leaked and repurposed by ransomware groups, wreaking havoc worldwide. If a government-mandated encryption backdoor was similarly exposed, the consequences could be catastrophic, with financial institutions, healthcare systems and national security infrastructure potentially open to attack.

The global domino effect

For those who aren’t convinced by the security argument against backdoors, consider this: history has shown repeatedly that government surveillance powers tend to expand beyond their original intent. A backdoor introduced to fight terrorism or child exploitation could easily be repurposed to monitor political activists, journalists or marginalized groups. Once such mechanisms are in place, it’s very difficult to wind them back, particularly in countries with weaker democratic institutions.

If the UK had succeeded in forcing Apple to introduce an encryption backdoor, other governments would almost certainly have followed suit. Authoritarian regimes around the world would demand the same access, arguing that if democracies can justify breaking encryption, so can they. Even within western democracies, once a precedent is set, it becomes nearly impossible to reverse.

And somewhat paradoxically, governments that advocate for strong cybersecurity measures by urging businesses and individuals to use encryption are often the same ones attempting to undermine it through backdoor mandates. Just weeks before the UK’s renewed push for encryption backdoors, the FBI and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency in the U.S. advised Americans to use end-to-end encryption in their communications to protect against cyber threats. The contradiction is stark.

Are backdoors really necessary?

Law enforcement agencies argue that encryption is a roadblock to their investigations. However, this is a problem that technology can solve without resorting to backdoors. Advanced cryptographic techniques such as Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) offer promising alternatives. FHE allows encrypted data to be analyzed without ever decrypting it, meaning authorities could conduct lawful investigations while preserving individual privacy and without compromising encryption protocols.

Other privacy-preserving technologies, such as secure multi-party computation (MPC) and zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs), offer ways to verify information without exposing sensitive user data. While neither MPC nor ZKPs function as direct replacements for content scanning, they provide alternative methods for accountability that do not introduce the systemic security risks associated with encryption backdoors. When combined with fully homomorphic encryption (FHE), these technologies could enable privacy-preserving verification mechanisms that balance security and user confidentiality.

Moving beyond an outdated debate

It is astonishing that in 2025, we are still having the same debate about encryption backdoors. The world has changed significantly in the past decade, with cyber threats becoming more sophisticated and digital privacy more important than ever.

Technology is leaps and bounds ahead of where it was even five years ago. Policymakers need to move beyond outdated strategies and recognize that there are better ways to balance law enforcement needs with individual rights.

The truth is, strong encryption protects everyone: private citizens, businesses and governments alike. Weakening it in the name of security, as the UK government ultimately forced Apple to do, is not only short-sighted but dangerous. Instead of pushing for backdoors, governments should collaborate with technologists to explore privacy-preserving solutions that enhance security without compromising fundamental freedoms.

It’s time to abandon the false dichotomy of privacy versus security. They are no longer mutually exclusive. The technology exists. The political will must follow.

Photo credit: Imilian / Shutterstock

Jeremy Bradley is COO, Zama.