Samsung PRAM Could Replace Flash Memory

A new, potentially less expensive substitute for flash memory may have taken a step closer to becoming reality today, as Samsung announced it had completed a prototype for a promising new, potentially more efficient non-volatile memory scheme.

Called phase-change random-access memory (PRAM), the patents for this concept date as far back as 1968. While the idea is conceptually simple, the problem for the last four decades has been finding the right balance of chemical materials that will behave as predicted on paper.

The basic concept, as outlined 12 years ago by its inventor, Dr. Stanford Ovshinsky, is to exploit the conductive properties of what's called chalcogenide ceramic material, capable of existing in two physical states, amorphous and crystalline. Varying the pulse of an electric current sent through this material will change its state, or its phase, instantaneously.

The process is not unlike Morse code: Send a high "dot" and the material assumes a crystalline state, with low resistivity - thus representing 0. Send a low "dash" and it becomes amorphous, with high resistivity - a 1. Originally, a "dash," in this instance was as long as 100 nanoseconds, although recent modifications in the material has enabled what scientists call "higher resolutions."

What makes the process inexpensive, at least theoretically, is the fact that the material in question is a ceramic - essentially clay made with not-too-uncommon elements. For PRAM, germanium is the most basic of these elements, often laced with antimony and telluride.

Ironically, it was the fall of the Soviet Union, a major germanium producer, which has been a major hurdle in the advancement of not only PRAM, but other ceramic conductivity technologies involving germanium during the 1990s. After having reached a peak of almost $2,000 per kilogram, according to U.S. government figures, germanium prices have since receded to around $600 per kilo.

By comparison, gold trades at about $19,000 per kilo, while copper -- the most common metal used in electrical devices -- trades today at about $7.59 per kilo.

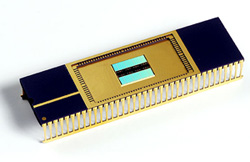

The schematic of PRAM is astoundingly simple. The wafer design is basically lateral, enabling engineers to focus not so much on fine-tuning the doping process as refining the lithography, concentrating now on 40 nanometers and lower.

The schematic of PRAM is astoundingly simple. The wafer design is basically lateral, enabling engineers to focus not so much on fine-tuning the doping process as refining the lithography, concentrating now on 40 nanometers and lower.

"PRAM will be a highly competitive choice over NOR flash, available beginning sometime in 2008," states Samsung in this morning's announcement. PRAM's originators, ECD Ovonics -- which licenses PRAM technology to Samsung, Hitachi, and others -- had originally pushed it as a replacement for all flash memory. So why is Samsung only touting it as a NOR flash replacement?

Right now, Samsung is the world's #4 producer of NOR flash, according to figures produced last month by analyst firm iSuppli, with only 6.4% worldwide market share. By comparison, #1 Spansion has 30.7% market share, with nearly five times Samsung's revenue in NOR: $655 million for the second quarter of this year, versus $136 million, by iSuppli's estimate.

Overall, the NOR market is rising healthily, analysts are saying, up 6% in overall revenues over the previous quarter. Meanwhile, the NAND flash market -- the much more common variety -- is where Samsung reigns supreme, with 46.2% market share, while the remaining companies in iSuppli's top eight divvying up the remainder.

NAND flash sales were depressed a bit in Q2 2006 -- down 15.7% over the previous quarter -- due mainly to lower average selling prices (ASPs). It's high competition that drives down selling prices, so conceivably, if Samsung's NAND flash position were to rise even more, it could stabilize the market, sending prices moderately higher and resulting in better margins. Samsung doesn't want to chop off the trunk of its own tree.

Meanwhile, Hitachi has no stake in flash memory, and has nothing to lose; and Intel may have at least considered selling off its flash memory units in order to concentrate its efforts on CPUs.

As Samsung cements its stake as Apple's leading supplier of flash memory of iPod, it not only has the most to gain from advancing PRAM - perhaps revolutionizing MP3 player architecture in 2009 and beyond - but also the most to lose.