Can the infosec community ever be as well-organized as digital criminals?

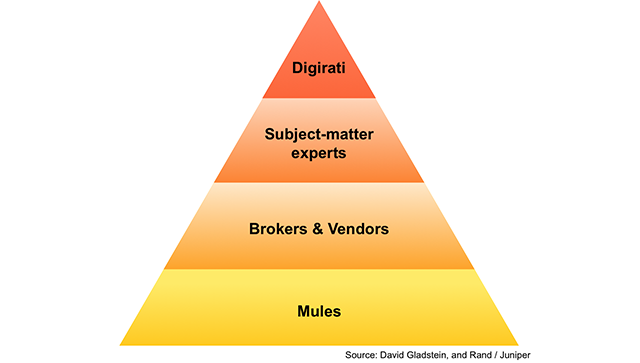

Brian Gladstein, a security marketing strategist at Carbon Black, discussed the question posed in this headline at RSA Conference 2018. In his presentation entitled "Endpoint Security and the Cloud: How to Apply Predictive Analytics and Big Data," Gladstein observes that digital crime is structured like an economy consisting of several tiers. At the top is the "Digirati," a term used by Gladstein for the class of high-ranking controllers responsible for executing digital attacks. The Digirati consists of the ones who hide on the network and gather information, usage patterns, and intel. They then share this information and build upon what knowledge they’ve already gathered from other actors in the online criminal community.

Below the Digirati are the subject matter experts. Malware writers, identity collectors, and individuals who hoard zero-day vulnerabilities and other exploits sit on this level of the digital crime economy. These individuals oftentimes sell access to their goods and services to the next tier, which consists of botnet owners, cashiers, spammers, and other brokers and vendors.

The final layer consists of buyers, observers and money mules, individuals who are oftentimes unwittingly enlisted by criminals to transport and launder stolen monies.

Reflections on the Digital Crime Hierarchy

Examining Gladstein’s digital crime hierarchy reveals some important observations. First and foremost, the world of online crime is extremely specialized and compartmentalized. Hardik Modi, senior director of the security engineering and response team at Arbor Networks, told Raconteur that most if not all components used in digital attacks "are routinely upgraded and customized for use in new campaigns, pointing to dedicated and separate teams of competent programmers." He went on to explain that bad actors usually hire out different teams at each link in the attack chain and pays them using Bitcoin. Such precautions help reduce the risk of the entire operation crumbling if one link gets busted.

Another important observation of Gladstein’s model for digital crime is the fact that digital crime mirrors corporate organizations in their structure. Per ZDNet, some attack chains support a 24-hour operation cycle and create call centers staffed with unknowing customer service representatives. And for those just starting out in digital crime, individuals can take training courses on how to hack a website and infiltrate a target system. Criminal organizations can then use those courses to vet or train candidates for a particular stage in the attack chain.

The parallels between legitimate organizations and digital crime don’t stop there, however. Just like corporate entities, criminal associations are known to reinvest their profits into other pursuits. According to a study conducted by Dr. Michael McGuire at the University of Surrey, bad actors reinvest approximately 20 percent of revenues into subsequent crime. In total, close to $300 billion funnel into various forms of offline crime. This activity has Dr. McGuire convinced that online crime is no longer just a business, as noted in his comment in Silicon Republic:

It’s much, much more than that. It’s like an economy which mirrors the legitimate economy. Increasingly, what we’re seeing is the legitimate economy feeding off the cybercrime economy. More concerning is evidence that cybercrime revenues are now significant enough to attract the attention of those who are ready to use them to fund more serious crime, such as human trafficking, drug production, or even terrorism.

Dr. McGuire found that bad actors used PayPal and similar platforms for money laundering purposes to fund these offline criminal pursuits.

How the Security Industry Compares

In comparison to digital crime, the security industry has no aggregate structure. Everyone is on their own, figuring out independently how to mitigate the same attacks and how to detect new threats as they emerge. This lack of cohesiveness is exacerbated by the fact that the industry doesn’t have enough security professionals to fill out its collective organization. According to ESG/ISSA research, 70 percent of security professionals say that the skills shortage has affected their particular place of work, while an almost equal majority (68 percent) said it has taxed them individually by blurring the line between their personal and professional lives. This effect led nearly four in 10 research participants to conclude that the skills gap is responsible for high rates of burnout among infosec personnel, thereby further contributing to an overworked and short-staffed workforce on which the security industry relies.

The security skills gap has some important trickle-down effects for the industry, as well. In a survey of 319 IT security decision makers by Dimensional Research on behalf of CIS and Tenable Network Security, 95 percent of organizations have trouble implementing digital security frameworks, with 57 percent of enterprises identifying a lack of trained staff as the most predominant factor for these challenges. The skills gap was followed by inadequate budget (39 percent) and lack of prioritization (24 percent). In the absence of adequate security staff and controls, companies leave themselves open to data exfiltration or attacks that abuse their business relationships in order to target additional companies, which places further burden on the industry.

Perhaps most significantly, the security industry is limited in its efforts by the absence of an international legal framework around digital crime. There have been proposals for guidelines that can help facilitate cross-border investigations, but some states refuse to sign them. As written in The New York Times, Russia in particular stands out because it has a record of working against accused criminals’ extradition to the West and actually hiring these actors into state-level positions.

How Security Organizations Can Even the Balance

Today the criminals appear to have the upper hand, given the security industry challenges describe above. But we collectively can take steps to fortify our respective organization against digital crime. First, we can work with education institutions to emphasize the importance of security education and create corresponding curricula. Second, the industry needs to work with governments to facilitate cross-border investigations into digital crime wherever possible.

Short of industry-wide action, individual security organizations can play a part in evening the balance with digital criminals. Much of the digital economy rests on the success of the Digirati and others successfully hiding in networks for as long as possible so that they can learn from their targets. These actors are stealthy in their attacks, but these intrusions aren’t silent. Organizations need to know where to look to detect them, have the skills and the latest security products to piece together disparate indications of a possible security incident, appropriately incorporate AI into security technology to help compensate for unfilled staff positions, and be open to sharing that information with enterprises and with other security technology companies.

Dr. Giovanni Vigna is Lastline’s co-founder and CTO, and also director of UC Santa Barbara's Center for Cybersecurity and a computer science professor at the school.

Dr. Giovanni Vigna is Lastline’s co-founder and CTO, and also director of UC Santa Barbara's Center for Cybersecurity and a computer science professor at the school.