A salute to a true managing editor: Walter Cronkite (1916-2009)

He would insist on the truth, so I won't embellish anything here: Walter Cronkite was not my hero growing up, but the guy playing for what I -- a boy trying to make sense of my world -- perceived as the other team. My hero was David Brinkley, one of only two other men I knew of besides myself (the other being Chet Huntley) who could command my mother's attention. As a toddler in the 1960s, my assessment of the true value of that feat alone may have actually directed me toward a career in journalism. So while my classmates' idea of a rivalry was between the Sooners and the Longhorns, or between the Beatles and the Monkees, the rivalry that gave me cause for excitement every day was between NBC News and CBS News. And Walter was the competition.

Later, as I truly studied electronic journalism, I would understand what it was that Cronkite had created and had contributed to the craft, early enough for me to use it in forging my career. Unlike most people in this business who wear the moniker "Managing Editor," Cronkite not only steered the ship of his news organization, but developed the principles by which a complete news product is expertly produced. He created the system of priorities by which news "packages" were conceived, organized, and delivered. And he would be the one reorganizing and reconfiguring that sequence, sometimes as late as seconds before air time, and on certain days literally in-between commercials. He saw his broadcast as a "front page," and he adapted it to the importance of the moment. He created the system of flexibility that should, if we were smart, be applied to the business of Internet journalism -- he knew the weights and measures that were necessary to obtain a balance between the stories people needed to know, and the stories people wanted to know.

If you think about it, not even Edward R. Murrow actually accomplished that; throughout Murrow's career, he privately expressed shame at the very fact that he did a celebrity interview show, Person to Person, as if that debased the character of a true newsman. While Cronkite will never approach Katie Couric in the category of celebrity interviews, he did at least understand why certain topics were popular, even when they were trivial compared to the Vietnam War and to America's race to the moon.

Cronkite also had an extremely keen insight as to what remained to be remedied in the business of electronic journalism. In the following excerpt from his 1996 autobiography A Reporter's Life, you can tell he saw the onset of Internet media on the horizon, but his biting assessment of the impending failure of television to do more than serve as what Murrow called "wires and lights in a box" could also be applied to the newer electronic medium 13 years later:

While television puts all other media in the shade in its ability to present in moving pictures the people and places that make our news, it simultaneously fails in outlining and explaining the more complicated issues of our day...For those who either cannot or will not read -- equally shameful in a modern society -- television lifts the floor of knowledge and understanding of the world around them. But for the others, through its limited exploration of the difficult issues, it lowers the ceiling of knowledge. Thus, television news provides a very narrow intellectual crawl space between its floor and its ceiling.

The sheer volume of television news is ridiculously small. The number of words spoken in a half-hour broadcast barely equals the number of words on two thirds of a standard newspaper page. That is not enough to cover the day's major events at home and overseas. Hypercompression of facts, foreshortened arguments, the elimination of extenuating explanation -- all are dictated by television's restrictive time frame and all distort to some degree the news available on television.

The TV correspondent as well as his subjects is a victim of this time compression, something that has come to be known as "sound-bite journalism." With inadequate time to present a coherent report, the correspondent seeks to craft a final summary sentence that might make some sense of the preceding gibberish. This is hard to do without coming to a single point of view -- and a one-line editorial is born. Similarly, a story of alleged misdeeds frequently ends with one sentence: "A spokesman denied the charges." No further explanation.

Television frequently repeats a newspaper story that is based on "informed sources." The newspaper may have carefully hedged the story with numerous qualifiers, but the time-shy newscast does not. More distortion.

...The answer to this informational dilemma in a free society is not immediately apparent...[and] is long-range, but desirable in any case. We must better educate our young people to become discriminating newspaper readers, television viewers and computer users. We must teach them that, to be fully informed, one must go to good newspapers, weekly newsmagazines, opinion journals, books and, increasingly, the Internet as well as television.By recognizing the advantages and limitations of each medium, this educated public would go multimedia seeking to slake its thirst for more information, and it would demand a better product to satisfy that thirst. Thus, in a market-oriented economy, demand would raise the quality of both print and broadcast news.

Viewed in that light, it's impossible to argue that Internet journalism has any excuse in its defense. Without time limits, and with the benefit of literary tools, it has the capacity for reason, explanation, and education that governed most of print media while Cronkite was a UP reporter during World War II. And with today's sheer volume of people either having been hired as journalists or having bestowed that title to themselves, you would think the odds would be in favor of the Internet's capacity to inform and educate its public. But let's be honest: No one has yet instituted the system of weights and measures, of flexibility and priority, that performs for Internet media the role that Cronkite created for The CBS Evening News.

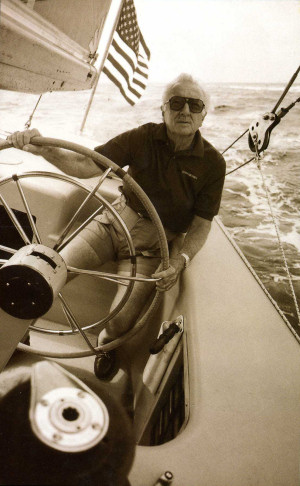

Essentially, it boils down to this: We don't get it yet. Most of us in the business of Internet journalism like to pretend we're riding this wave of change, but nobody really has his hands on the tiller at the moment. Some of us think there's some extraordinary value in being "alternative" journalists, as if proclaiming oneself in the "Other" or "Miscellaneous" category carries some mythical gravitas -- as if the fact that we're not as square as Uncle Walter somehow makes us better. It's a lie we tell to ourselves, and it's wearing thin.

What too often determines our priorities is what makes a clever headline -- we've embraced and extended "sound-bite journalism" to the extent that now, we spend valuable hours crafting the cutest or most titillating or most offensive, pot-stirring statement we can in twelve words or less. That's mostly for the benefit of Google News or some aggregator to whom we've bequeathed the job of promoting us, for most of us are just too lazy to work that problem out for ourselves. It's not that we think it's beneath us, as Murrow did. We just don't get it, and we're too high on our own adrenaline to admit it.

The fact that we marvel at one service's capacity to flush out volumes of data, in 140-character-or-less nuggets of often indigestible tripe, with the level of trust and awe that the previous generation entrusted to a man sitting at a desk who made some modicum of sense, stands as testament to the fact that we do not have a handle on how the news can or should be delivered to this generation.

In the Internet realm, there is no equivalent of the CBS Evening News or Huntley-Brinkley Report, or for that matter no New York Times (not even The New York Times itself), because none of us in this business has stepped up to the plate where Cronkite stood. We in this modern era have not worked out a way to deliver the information an informed public requires for its survival, plus the news that interests the public, in a single, succinct package with authority, wisdom, and confidence. That is not to say it cannot be done. If those of us who would dare wear Cronkite's title were to truly do it justice, then it is our duty and responsibility to solve this dilemma. But we have a choice: We can either continue to craft nifty headlines topping 300 words of fluff that trail off with "A spokesman denied the charges" -- which, in my view, is the journalistic equivalent of flipping burgers -- or we can learn once again how to be real journalists in a real world.

Walter Cronkite left our world in peace Friday night, knowing he had accomplished what he had set out to do, and with pride in his work. He remains the model for what every true journalist should ever hope to achieve.