Congress: Should cell phone exclusivity contracts be illegal?

Exclusive cell phone sales and distribution contracts, such as the one between AT&T and Apple Inc. for all models of iPhone, are solely responsible for the quickening pace of innovation in the American handset market, or solely responsible for its imminent demise -- solely. That's the black-and-white nature of the arguments raised before the Senate Commerce Committee last Wednesday, as executives from the nation's second largest carrier and two smaller ones joined industry advocates in debating whether locking out carriers' access to popular phones is good for competition and good for the consumer.

"Today, when you sit down at a computer and you access a broadband connection, you're not told by your broadband provider that you have to have a Dell or an HP or an Apple in order to access the network," stated Sen. John Kerry (D - Mass.), the former presidential candidate who chaired a portion of Wednesday's hearing. "And when you purchase a wireless phone in Asia or Europe, you typically don't buy it through a wireless carrier. You purchase it separately from the manufacturer or from an outlet."

"Today, when you sit down at a computer and you access a broadband connection, you're not told by your broadband provider that you have to have a Dell or an HP or an Apple in order to access the network," stated Sen. John Kerry (D - Mass.), the former presidential candidate who chaired a portion of Wednesday's hearing. "And when you purchase a wireless phone in Asia or Europe, you typically don't buy it through a wireless carrier. You purchase it separately from the manufacturer or from an outlet."

Regardless of the fact that many broadband subscribers rent their cable modems through their carrier, this state of affairs -- where every device is available to everyone everywhere -- seems to Sen. Kerry like an ideal state of affairs.

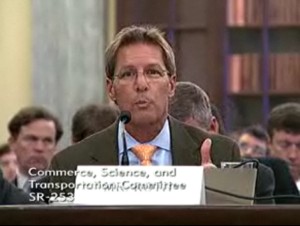

But on the other side of the bench was Paul Roth, President of AT&T Retail Sales and Services, who is one of the principal architects and defenders of his company's contract with Apple (the exact terms of which senators last week were unsuccessful at prying loose). Roth's principal argument was difficult to rebut: If you level the playing field nationwide, you end up driving handset prices up and the incentive to make better handsets down.

"Exclusive device deals lead to lower prices. Consumers pay well under what AT&T pays Apple for the iPhone. It's a standard US industry practice for the device [to be] sold below its cost, in return for a two-year agreement where the subsidy that made the initial price possible is recovered over the term of the agreement," Roth testified. "In the past two years that the iPhone has been exclusive to AT&T, the price of the iPhone has gone from $399 to $199, and just last week to $99, all while exclusive to AT&T. And with the iPhone at $99, prices of other devices, including other exclusive devices, have dropped and will continue to drop in response to that."

"Exclusive device deals lead to lower prices. Consumers pay well under what AT&T pays Apple for the iPhone. It's a standard US industry practice for the device [to be] sold below its cost, in return for a two-year agreement where the subsidy that made the initial price possible is recovered over the term of the agreement," Roth testified. "In the past two years that the iPhone has been exclusive to AT&T, the price of the iPhone has gone from $399 to $199, and just last week to $99, all while exclusive to AT&T. And with the iPhone at $99, prices of other devices, including other exclusive devices, have dropped and will continue to drop in response to that."

Along with innovation comes the risk of lack of success -- a risk that handset manufacturers in this economy are unwilling to assume completely on their own, Roth pointed out. So AT&T and the other competitors in the "Big Four" -- Verizon Wireless, Sprint, and T-Mobile -- offer exclusivity deals to manufacturers, he said, knowing it will drive them to produce handsets with features that competitors' models may lack.

Roth also went so far as to argue this: If AT&T and other carriers did not seek exclusivity by demanding features such as touchscreens, with the sole exception being Apple (which all agreed to have initiated the iPhone deal), manufacturers would not have offered or even created these features on their own.

As Roth went on, "We often ask for innovative features or design which requires a manufacturer to create an entirely new product, and our requirements are often the catalyst for innovation. To build really new and innovative devices creates risks for manufacturers, and the manufacturers are seeking a partner to share that risk with them. They ask us to commit both technical and financial resources, and make volume commitments, all without the assurance that the device will be a success. AT&T competes with foreign carriers like Deutsche Telekom and Vodafone for the attention of these manufacturers, to bring innovative devices first to consumers in the United States. It's not an accident that the iPhone...launched first in the United States. We took a risk with Apple on the iPhone, that it would be a big success for consumers. And consumers were the ones who benefitted from that."

But beside Roth on the witness table were executives from two other carriers serving mainly rural areas, including US Cellular President and CEO Jack Rooney. Claiming that the Big Four carriers were doing no less than hijacking the industry, Rooney argued, "Exclusive arrangements are especially damaging to rural citizens because oftentimes the biggest carriers don't offer any service at all, and so the product is unavailable to that consumer. When rural consumers buy an exclusive phone from one of the bigger carriers, they frequently must accept an inferior network as a tradeoff -- a tradeoff no consumer should be compelled to make.

"There is harm in urban areas as well. Consumers who desire an iPhone or a BlackBerry Storm smartphone cannot use it on our network, even if they prefer our service," Rooney continued. "We do not understand how the public can possibly be served by such a practice. If you take away nothing else from this meeting, I want you to understand a central goal of policy makers should be to enable consumers to buy the handset they want, and choose the service that best suits their needs."

"There is harm in urban areas as well. Consumers who desire an iPhone or a BlackBerry Storm smartphone cannot use it on our network, even if they prefer our service," Rooney continued. "We do not understand how the public can possibly be served by such a practice. If you take away nothing else from this meeting, I want you to understand a central goal of policy makers should be to enable consumers to buy the handset they want, and choose the service that best suits their needs."

Roth later countered by arguing that AT&T also serves rural areas as well, blanketing 90% of the nation, and soon 95% after it acquires some Alltel assets from VZW. But Rooney agreed that the US market was vast, which should be catalyst enough, he said, for handset manufacturers to pursue this market without exclusivity as an incentive.

"I've heard that exclusive arrangements drive innovation. This is counter-intuitive. Every manufacturer desires to sell its product to the widest possible audience," testified Rooney. "If handset exclusivity did not exist, would any manufacturer refuse to invest in great devices knowing that there was currently a handset market of nearly 300 [million] users in the United States? Any handset maker that invents a great device receives intellectual property protection, and that confers a tremendous financial incentive to build a winning product."

Supporting Rooney's claims was Penn State Professor of Telecommunications and Law Robert M. Frieden, who pointed out that one of today's common tenets of exclusivity agreements consists of arrangements between a carrier and manufacturer to limit functionality, as evidenced by the growing list of functions you cannot do on an iPhone.

"Near-exclusive reliance by wireless carriers and their agents on a single business model, which combines wireless service and handsets used to access the service, strongly influences what kinds of services the handset can perform, and what kind of software the subscriber can download," said Prof. Frieden. "This combination of handset and service also creates incentive for carriers to secure exclusive distribution rights for choice devices such as the Apple iPhone. It motivates carriers to favor ways to recoup their handset subsidies rather than to concentrate on offering unconditional access to the features within the handset, or services available by downloading software and content to the handset."

"Near-exclusive reliance by wireless carriers and their agents on a single business model, which combines wireless service and handsets used to access the service, strongly influences what kinds of services the handset can perform, and what kind of software the subscriber can download," said Prof. Frieden. "This combination of handset and service also creates incentive for carriers to secure exclusive distribution rights for choice devices such as the Apple iPhone. It motivates carriers to favor ways to recoup their handset subsidies rather than to concentrate on offering unconditional access to the features within the handset, or services available by downloading software and content to the handset."

Frieden cited the FCC's 1968 Carterfone decision, which enabled customers for the first time to purchase telephones other than those produced by Western Electric -- at the time, AT&T's sole manufacturer. The principle of that decision, the professor said, was that utilities that provide a service should have no monopoly on the device that produces that service.

"Television broadcasters have no right to restrict consumers from watching cable and DVDs. Likewise, no personal computer manufacturer or software vendor can regulate what consumers see on their monitors, and what services they can access. Applying the Carterfone policy to wireless would stimulate innovation in handset design, promote competition, and motivate carriers to make their networks more accessible," stated Frieden.

The argument against Frieden is that the wireless industry, unlike the wireline phone industry in 1968, does not need the FCC's intervention in order to create competition. That argument was presented by Progress & Freedom Foundation Senior Fellow Barbara Esbin, with a tone that at times indicated she seemed annoyed at Frieden's and Rooney's arguments, and at times that she just had a headache and would like to have gone home.

"Consumers will remain protected from demonstrable anti-competitive activity or unfair and deceptive practices in this sector by our antitrust and consumer protection authorities. The FCC has repeatedly found the wireless marketplace to be effectively competitive -- not perfectly competitive, but effectively competitive," Esbin testified. "Carriers are willing to pay for exclusive arrangements because offering subscribers a hot new handset is a way to differentiate their services. The FCC has acknowledged that product differentiation is a natural competitive response by carriers to customer churn. Churn itself is a sign of competition, and the exclusive arrangements are simply a feature in an intensely competitive market. And handset manufacturers benefit from the exclusives by being able to develop the initial version of a device for one type of network, ensuring both speed to market and some control over the user experience. Guaranteed minimum order from the manufacturer, another common feature, can remove some of the risks associated with a new product offering, thus permitting riskier and more innovative designs."

"Consumers will remain protected from demonstrable anti-competitive activity or unfair and deceptive practices in this sector by our antitrust and consumer protection authorities. The FCC has repeatedly found the wireless marketplace to be effectively competitive -- not perfectly competitive, but effectively competitive," Esbin testified. "Carriers are willing to pay for exclusive arrangements because offering subscribers a hot new handset is a way to differentiate their services. The FCC has acknowledged that product differentiation is a natural competitive response by carriers to customer churn. Churn itself is a sign of competition, and the exclusive arrangements are simply a feature in an intensely competitive market. And handset manufacturers benefit from the exclusives by being able to develop the initial version of a device for one type of network, ensuring both speed to market and some control over the user experience. Guaranteed minimum order from the manufacturer, another common feature, can remove some of the risks associated with a new product offering, thus permitting riskier and more innovative designs."

Next: Could exclusivity bleed into the computer realm?