Internet Explorer 9, the HTML 5 browser: Better than half-way there

[Today's delay in Betanews bringing you Internet Explorer 9 news was brought to you as a public service by the Cable Modem: Your Best Friend When It's Crunch Time. Remember, where there's smoke, there's a Comcast cable modem. Smell one today.]

It is perhaps the unlikeliest scenario any technologist could imagine as recently as two years ago: Microsoft evangelizing developers to embrace Web standards by helping it to build its Web browser. Although one of the first browsers to be distributed for free, Internet Explorer has never been open source. Historically, it's always been ready when it's ready; its value proposition has been to the consumer who prefers convenience over adaptability; and when the fact that it was dirt slow was pointed out, the response typically was, the consumer isn't going to care.

Today, the value proposition started to take shape for IE9, the browser that in an earlier era didn't need a value proposition. Microsoft's strategy, which premiered today at MIX 10, was to seize control of tomorrow's key talking point, HTML 5 compliance and compatibility -- to make HTML 5 identifiable with Internet Explorer. In fact, IE General Manager Dean Hachamovitch's greeting sentence to MIX 10 attendees this morning wasn't without the term "HTML 5."

"When we started looking deeply at HTML 5, we saw that it enabled a whole new class of applications," was Hachamovitch's second sentence. "These applications will stress the browser runtime and hardware, as today's sites just don't. We quickly realized that doing HTML 5 right -- our intent -- was more about designing around what HTML 5 applications will need, rather than a particular set of features. Done right, HTML 5 applications will feel more like real apps than Web pages, and our approach to HTML 5 is to make standard Web patterns that developers already know and use, just run faster and better by taking advantage of PC hardware through Windows."

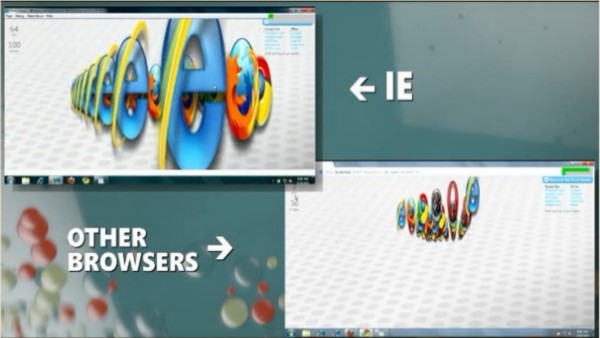

Developers have always known that Microsoft has always had the capability to leverage its mastery of Windows APIs to build smoother applications. But as other Microsoft applications have weaned themselves off of the old Win32 dependencies, such as rendering using the old GDI and GDI+ libraries, Internet Explorer has fallen further and further behind. In fact, you could make the case that Silverlight gives Web developers opportunities to use the modern rendering libraries that IE should be using now natively.

Soliciting general developers' help in improving IE (some will say for the first time), Microsoft today began distributing the bare-bones chassis of the IE9 Web browser -- no frills, no features, not even bookmarks. Just a rendering engine in a window. With Google Chrome, Apple Safari, and now even Opera having made effective cases for the Web being "the platform," Microsoft desperately needs to resume defining the platform before someone else ends up defining it instead.

But one element of Microsoft's IE message remains the same even today: Those areas where the competitors say they have the advantage, may not be all that important to end users. Case in point: just-in-time compilation, the factor that has catapulted Mozilla Firefox and WebKit-based browsers such as Safari and Chrome into today's speed race.

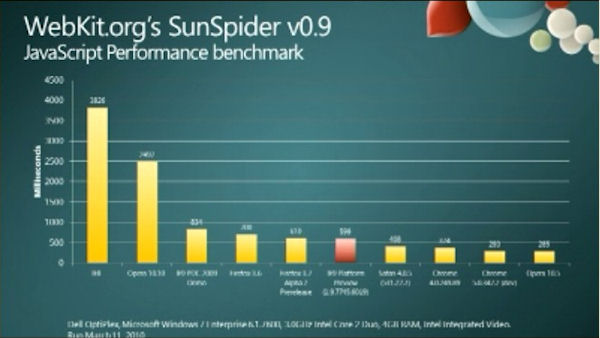

For example, Hachamovitch did cite the IE9 chassis' speed improvement on the widely accepted SunSpider performance test, created by the originators of the open source WebKit engine. On Microsoft's chart, Opera is the fastest performer on the SunSpider, followed by a Chrome 5 dev build, a Chrome 4 stable build, and the latest Safari 4.0.5, released late last week by Apple (apologies for the fuzzy screenshot of Microsoft's chart). So yes, IE9 comes in fifth, rather than dead last. But the difference isn't that much of a difference, he said:

"It's interesting to note that the gap between IE9 and some of the other browsers to its right is about an eye-blink -- it's about 300 ms. And it took 70 seconds to identify that 300 ms difference."

When it comes to HTML 5, Microsoft wants to be perceived now as leading that standard. But with respect to standards at large, the company's position remains unchanged from last year: As long as Web standards are up in the air, compliance is a foggy term anyway. Today, Hachamovitch implied that if the goal of standards bodies were the same as Microsoft's goal of one language, the fog would be lifted:

"Developers want to use the same HTML, the same script, and the same markup across browsers. That's the goal of standards and interoperability. No need for different code paths for different browsers. That's a key goal for HTML 5. We love HTML 5 so much, we want it to actually work. In IE9, it will. We want the same HTML, the same script, the same markup to just work across browsers. So in IE9, we'll do for the rest of the Web platform what we did for CSS 2.1 in IE8. Now, at the same time, we want to be responsible about the standards that are still emerging, the standards that are in committee, and the standards that are partially implemented, often in different ways across browsers. So to make decisions on this front, we started from data."

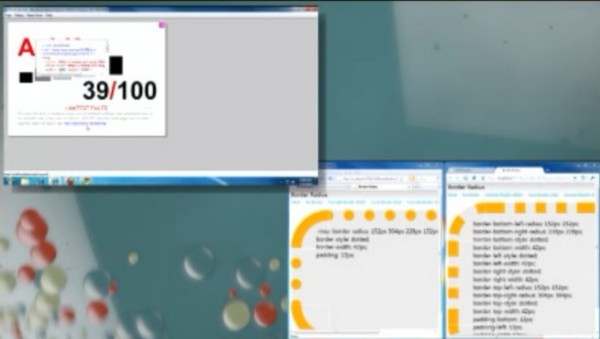

As an Acid3 test runs in the background (it's not done yet), Dean Hachamovitch demonstrates how 'standards' support varies between even Firefox and Chrome (lower right) for the same markup.

The IE9 team leader went on to describe an internal tool that measured the script activity on 7,000 active Web sites. The telemetry that it received showed, for instance, that the #1 method in use was indexOf(), on 94% of sites measured. Number 17 on the list, used by 65% of sites, was addEventListener, a method that's key to W3C's advanced event registration model, but not yet supported in IE8.

"Because we started from data, what developers like you really use was our starting point for what to support." As a result, the IE9 chassis passed 578 out of 578 in the CSS3.info selectors test, putting it now on a par with Firefox. That's important, Hachamovitch noted, because developers want that one language -- one CSS, one HTML -- to work with for all browsers across the board.

Meanwhile, the IE9 preview posts a 55% score on the Acid3 standards compliance test -- up from 20% for IE8, and 12% for IE7. The latest stable Firefox, by comparison, scores 94% on this test; and Safari, Chrome, and Opera all score 100%. Could the CSS3.info test be fair, and the Acid3 test unfair?

Meanwhile, the IE9 preview posts a 55% score on the Acid3 standards compliance test -- up from 20% for IE8, and 12% for IE7. The latest stable Firefox, by comparison, scores 94% on this test; and Safari, Chrome, and Opera all score 100%. Could the CSS3.info test be fair, and the Acid3 test unfair?

"Some people use Acid3 as shorthand for standards support. Acid3 is kind of interesting, it exercises about a hundred details of a dozen different technologies. Some of them are under construction, others less so," Hachamovitch said. He added a promise that Acid3 scores will continue to improve "as we make more of the markup that developers actually use, work."

Next: Offloading processing to the background and to the GPU...