Without the fastest JavaScript, can Opera 10 RC still lay claim to speed?

"At Opera, we love speed," reads the beginning of a March 2009 blog post from Opera Software Product Analyst Roberto Mateu. "We work hard to make our browser faster with features that speeds you up."

"At Opera, we love speed," reads the beginning of a March 2009 blog post from Opera Software Product Analyst Roberto Mateu. "We work hard to make our browser faster with features that speeds you up."

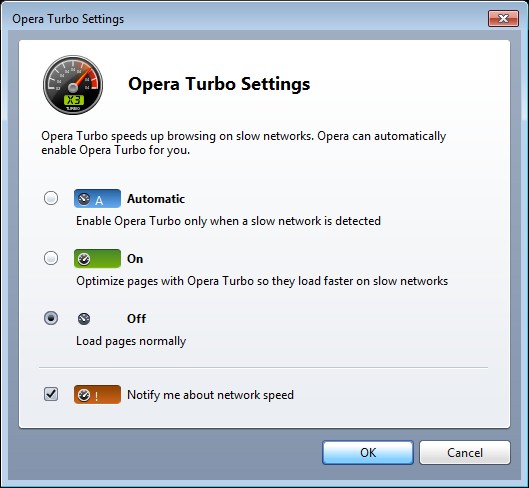

That particular lead-in was for a post discussing the inclusion of Opera Turbo, a feature originally created to expedite rendering in mobile browsers, in the latest Opera 10 desktop edition. Up until recently, Opera was the browser noted for elegance, adherence to accepted Web development standards, and speed; and with regard to the latter, the company is still touting Turbo as the top addition to the first release candidate of version 10, released yesterday.

On Opera Mini, Turbo can be a real lifesaver, especially in limited bandwidth situations. It uses a connection to Opera's own proxy servers, where contents are cached or rendered with higher-speed processors than you'd find on the usual smartphone, to produce legible pages faster. But in the PC world, broadband is becoming more common (especially in its native Norway, much more so than in the US); so for users there, Turbo mode is likely to come in handy only as a fallback during high traffic times or near-outages.

Betanews tests Wednesday morning on the latest build of Opera 10 RC reveal very heavy pixilation in downloaded images, probably due to the quality factor of JPEG rendering being turned down to expedite page loads. However, our initial tests do show that when Turbo Mode is turned on, and its default acceleration factor reads "x3," page load and render times are as much as 358% the speed as when Turbo is turned off, 58% faster than what the mode actually indicates. This is the case even when rendered pages do not contain images.

Already, Opera 10 may be the fastest rendering browser for Windows being tested in the field. In our tests this morning, build 1733 running in Windows 7 RTM showed it could render pages with Turbo Mode turned off at 426% the speed of Internet Explorer 7 running in Windows Vista SP2 (the index browser for our relative tests). By comparison, the latest development build of Google Chrome 4 we've tested renders the same test pages about 28% slower than Opera 10 RC, with a performance score in rendering of 3.76 versus 4.26.

But just as broadband plays a bigger role in people's lives these days, JavaScript plays a bigger role in more people's Web pages. And that's where Opera simply hasn't competed against any of the other Windows browsers, not even Firefox -- last year, Opera's performance against Firefox won it critical accolades. In overall test scores on the Windows 7 RTM platform, the latest dev build of Google Chrome 4 scored 15.20 on our index versus 5.36 for Opera 10 RC, meaning the latest Chrome delivers 284% the general performance of the latest Opera.

Users who remain loyal to Opera -- and there are many -- have had to remain content for now that the company may devote new attention to its JavaScript interpreter for round 11 of its browser.

As far back as last February, Opera developer Jens Lindstrom acknowledged that the company's once venerable Futhark JavaScript engine isn't up to modern standards: "When Opera's current ECMAScript engine, called Futhark, was first released in a public version, it was the fastest engine on the market. That engine was developed to minimize code footprint and memory usage, rather than to achieve maximum execution speed. This has traditionally been a correct trade-off on many of the platforms Opera runs on. The Web is a changing environment however, and tomorrow's advanced Web applications will require faster ECMAScript execution, so we have now taken on the challenge to once again develop the fastest ECMAScript engine on the market."

Half a year later, we've heard very little about the progress of the new JavaScript/ECMAScript engine that Lindstrom dubbed "Carakan." But the company may have to clear out its Opera 10 development cycle before it can devote full resources to the engine that could get Opera back in the game.