Fukushima Daiichi requires a Manhattan Project approach to avoid another nuclear accident

This is my sixth column about the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident that started last year in Japan following the tsunami. But unlike those previous columns (1,2,3,4,5), this one looks forward to the next Japanese nuclear accident, which will probably take place at the same location.

This is my sixth column about the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident that started last year in Japan following the tsunami. But unlike those previous columns (1,2,3,4,5), this one looks forward to the next Japanese nuclear accident, which will probably take place at the same location.

That accident, involving nuclear fuel rods, is virtually inevitable, most likely preventable, and the fact that it won’t be prevented comes down solely to Japanese government and Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) incompetence and stupidity. Japanese citizens will probably die unnecessarily because the way things are done at the top in Japan is completely screwed up.

Understand that I have some cred in this space having worked three decades ago as an investigator for the Presidential Commission on the Accident at Three Mile Island and later wrote a book about that accident. I also ran for 20 years a technology consulting business in Japan.

Too Much Cleanup, Not Enough Time

Here’s the problem: In the damaged Unit 4 at Fukushima Daiichi there are right now 1,535 fuel rods that have yet to be removed from the doomed reactor. The best case estimate of how long it will take to remove those rods is three years. Next to the Unit 4 reactor and in other places on the same site there are more than 9,000 spent fuel rods stored mainly in pools of water but in some spots exposed to the air and cooled by water jets. The total volume of unstable nuclear fuel on the site exceeds 11,000 rods. Again, the best estimate of how long it will take to remove all this fuel and spent fuel is 10 years -- but it may well take longer.

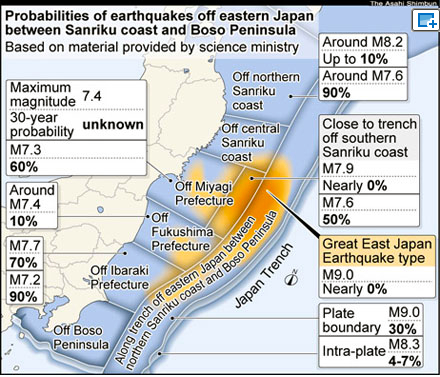

Fukushima has always been a seismically active area. Called the Japan Trench Subduction Zone, it has experienced nine seismic events of magnitude 7 or greater since 1973. There was a 5.8 earthquake in 1993; a 7.1 in 2003; a 7.2 earthquake in 2005; and a 6.2 earthquake offshore of the Fukushima facility just last year, all of which caused shutdowns or damage to nuclear plants. Even small earthquakes can damage nuclear plants: a 6.8 quake on Japan’s west coast in 2007 cost TEPCO $5.62 billion.

But last year’s 9.0 earthquake and tsunami made things far worse, further destabilizing the local geology. According to recently revised estimates by the Japanese government, the probability of an earthquake of 7.0 magnitude or greater in the region during the next three years is now 90 percent. The Unit 4 reactor building that was substantially damaged by the tsunami and subsequent explosions will not survive a 7.0+ earthquake.

An earthquake of 7.0 or greater is likely to disrupt cooling water flow and further damage fuel storage pools possibly making them leak. If this happens the fuel rods will be exposed, will get hotter and eventually melt, puddling in the reactor basement and beneath the former storage ponds. This is a nuclear meltdown, which will lead to catastrophic (though non-nuclear) explosions and the release of radioactive gases, especially Cesium 137.

The amount of Cesium 137 in the fuel rods at Fukushima Daiichi is the equivalent of 85 Chernobyls.

To review, there is a 90 percent chance of a large earthquake in the minimum three years required to remove just the most unstable part of the fuel load at Fukushima Daiichi. The probability of a large earthquake in the 10+ years required to completely defuel the plant is virtually 100 percent. If a big earthquake happens before that fuel is gone there will be global environmental catastrophe with many deaths.

A Cultural Problem

Let me explain how something like this can happen. For 20 years I ran with a partner a consulting business in Japan serving some of that country’s largest companies. Here is how our business worked:

1. A large Japanese company would announce a bold technical goal to be reached in a time frame measured in years, say 5-10. This could be building a supercomputer, going to the Moon, whatever.

2. Time passes and in quarterly meetings team leaders are asked how the project is going. They lie, saying all is well, while the truth is that little progress has been made. Though money is spent, sometimes no work is done at all.

3. The project deadline eventually approaches and a junior team member is selected to take the heat, admitting in a meeting that there has been very little progress, taking responsibility and offering to resign. The goal will not be reached, the company will be embarrassed.

4. In a final attempt to avoid corporate embarrassment, the company reaches out to me: surely Bob knows some Silicon Valley garage startup that can build our supercomputer or take us to the Moon. Money is no object.

5. Sure enough, there often is such a startup and the day is saved.

Fix Now, or Pay Later

It’s my belief that this is exactly what’s going on right now at Fukushima Daiichi. The very logic of time and probability that scares the bejesus out of me is being completely ignored, replaced with magical thinking. Organizations are committing to fix the current disaster and avoid the next disaster when in fact they are probably incapable of doing either. Lies are being told because Japanese government and industry are more afraid of their vulnerabilities being exposed than they are concerned about citizens dying. Afraid of being embarrassed, they press forward doing the best that they can, praying that an earthquake doesn’t happen.

This is no way to approach a nuclear catastrophe. What’s even worse is this approach isn’t unique to Japan but is common in the global nuclear industry.

Time is critical. What’s clearly required in Fukushima is new project leadership and new technical skills. Some think the Japanese military should take over the job, but I believe that would be just another mistake. The same foot dragging takes place in the Japanese military that happens in Japanese industry.

Fukushima Daiichi requires a Manhattan Project approach. The sole role of the Japanese government should be to pay for the job. A single project leader or czar should be selected not from the nuclear industry and that leader should probably not be Japanese. Contracts should be let to organizations from any country on equal merit so only the best people who can move the quickest with safety get the work. Then cut the crap and get it done in a third or half the time.

But that’s not how it will happen. In Japan it almost never is.

Reprinted with permission

Photo Credit: Franck Boston/Shutterstock

Robert X. Cringely has worked in and around the PC business for more than 30 years. His work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Forbes, Upside, Success, Worth, and many other magazines and newspapers. Most recently, Cringely was the host and writer of the Maryland Public Television documentary "The Tranformation Age: Surviving a Technology Revolution with Robert X. Cringely".

Robert X. Cringely has worked in and around the PC business for more than 30 years. His work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Forbes, Upside, Success, Worth, and many other magazines and newspapers. Most recently, Cringely was the host and writer of the Maryland Public Television documentary "The Tranformation Age: Surviving a Technology Revolution with Robert X. Cringely".