Apple Safari 4 beta raises the bar for speed, compliance

We've been hearing quite a lot from every browser manufacturer, including Microsoft and Mozilla, about the incredible speed increases that eventually, pretty soon now, right around the corner, will be realized the moment one of them bites the bullet and installs a new, faster JavaScript interpreter. Well, consider the bullet officially bitten. Betanews tests of Apple's new beta of Safari for Windows, using a freshly cleaned Windows Vista SP1 virtual machine "white box," demonstrates significant speed improvements even over previous Safari versions, which were already quite fast.

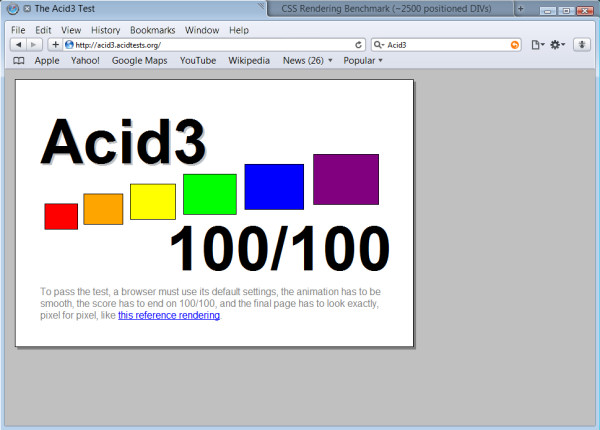

What's more, the Safari 4 beta (reviewed by Tim Conneally Wednesday afternoon) scored a perfect 100% on the Web Standards Project's Acid3 test -- the industry's most respected indicator of whether a browser renders text the way the engineers of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript intend it to.

While Safari is officially the world's #3 Web browser, according to the latest data from analytics and research firm NetApplications, that's mainly because of two reasons: It's the Web browser for the iPhone, and it's the principal browser for the Mac. Its Windows user base is relatively negligible. But that might change if Apple were suddenly to emerge with a value proposition that distinguishes it from the rest of the pack, even from Firefox. If the code of Safari Beta 4 stays stable through its testing period, Apple may very well have one.

In our initial tests this afternoon, we pitted the latest Safari 4 beta for Windows against the latest production versions (not betas) of the other four major Windows-based browsers: Internet Explorer 7 (fully updated), Firefox 3.06, Opera 9.63, and the most recently updated Google Chrome. We gave each browser the same battery of tests: a CSS rendering benchmark designed by the British Web design training firm HowToCreate; a JavaScript speed test by Irish Web developer Sean Patrick Kane; and the familiar Acid3 standards test (which measures compliance, not speed).

A virtual machine is a handicap in itself for benchmarking purposes, but what's important is that its an equivalent handicap for each of the contenders. So what matters is the relative speed of the browsers with respect to one another; the proportion of how much faster one is than the other will probably hold reasonably true in any production environment. The host system in our test uses a 2.4 GHz Intel Core 2 Quad Q6600 with 3 GB of DRAM.

While Opera 9.63 put in a good CSS rendering score of 10 microseconds (ms), after a 250 ms load time (the interval spent in preparing JavaScript to run), Safari 4 blew right past Opera with a 7 ms render time and a 54 ms load time. This compared to 26 ms render time and 177 ms load time for Google Chrome, 61 ms render time and 400 ms load time for Firefox 3.0.6, and a lumbering 131 ms render time and 555 ms load time for IE7. That means IE7 was 17 times slower than Safari at CSS rendering.

In the S.P. Kane test, which uses a battery of common JavaScript tasks executed in sequence, Safari also blew past its competitors with a score of 174 ms, versus 348 ms for Chrome, 381 ms for Opera, 499 ms for Firefox, and a thumb-twiddling 1533 ms (a second and a half) for IE7. If you can imagine the sound of CBS' famous 60 Minutes stopwatch in your mind, Safari can complete a battery of JavaScript instructions in the interval between two of those ticks, while you could count eight of them before IE7 got its work done.

While Firefox 3.1 is due to include the TraceMonkey JavaScript interpreter, whose initial internal tests are said to reveal orders of magnitude greater speed than with the 3.0 series, no public beta has been released yet with TraceMonkey included. Now may be a good time.

Finally, in the all-important Acid3 test, yes, Safari 4 turned in a perfect 100% score. This compared to an 85% for Opera, 79% for Chrome, 71% for Firefox, and an appreciably pitiful 12% for IE7.

There is a clear-cut reason -- at least one in the works -- for Windows users to have a browser made by Apple. But as with other Apple software (QuickTime and iTunes), regardless of whether the user chooses not to have Apple's automatic updater during the setup routine, once again, it gets installed anyway.

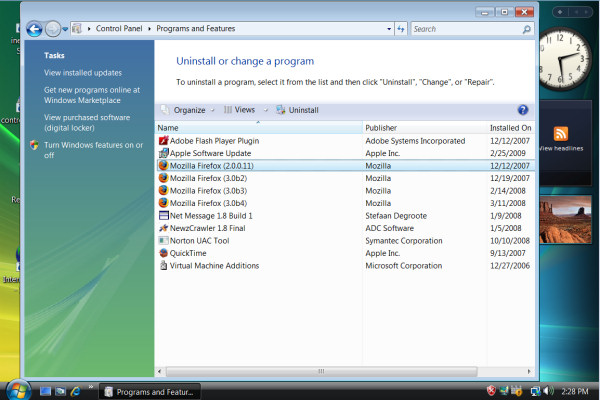

Apple Software Update showed up in our list of uninstallable programs, even though we explicitly requested it be omitted. Just as an experiment, we wanted to see whether Apple's setup routine would recognize Software Update was already present during a separate Safari installation process -- in other words, would it still give you the option to not have automatic updating, even if you didn't request it in the first place, if it's already installed. Indeed, Apple's setup program omits the option to disinclude Apple Software Update if it's installed -- that's not to say it "greys" the option, it leaves it off. So Apple clearly knows what it's doing, and why.

It would be easier to trust Apple to do a better job with its Web browser if it would have its software do what we lowly Windows users ask it to do.

Despite that, Apple's early victory could bode well for the company at a very opportune time: If the European Commission proceeds as it has threatened to do, Microsoft could be compelled, at least insofar as Europe is concerned, to offer Windows 7 customers the opportunity to install each of the major alternative browsers instead of Internet Explorer 8. If that's the case, Microsoft may find itself at least linking to, if not directly including, a major piece of Apple software with its operating system. And that means Apple Software Update could be installed by those who choose Safari...and that means they could wake up one day, as many already have, and find something new and unexpected called MobileMe.