The Big Brother in your pocket: How a US company secretly tracks and rates half of the world's mobile users

Imagine a hidden system that tracks and scores you based on every phone call you make or take. It might sound like something straight out of a Black Mirror episode and remind you of China's controversial social credit system. But surprisingly, half of the world's mobile phone users are already part of a similar system, and many of them are Europeans, who are supposed to enjoy the strongest privacy protections.

NOYB, a privacy advocacy group, has filed a lawsuit against the US company TeleSign, a Belgian telecom provider BICS, and their mutual parent Proximus. They claim these companies are unauthorizedly profiling billions of phone users to assign them a 'reputation' or 'trust' score.

This score can affect your access to online services: If your score is bad, you may be blocked from accessing certain online platforms, or be subject to additional checks which those with better scores won’t have to go through. These restrictions are imposed by TeleSign’s partners, which reportedly include Microsoft, TikTok, Skype, LinkedIn and SalesForce. So, who are BICS and TeleSign and what do they do exactly?

BICS is a Belgian telecom giant, which connects networks of mobile phone providers in over 200 countries. By doing so, BICS gains access to personal information of tens of millions of customers. BICS gets to know how often people make calls, how long they talk, how long they don’t use their phones, where they are, and when someone calls them. This data is then shared with TeleSign, which assigns ‘reputation scores’ to phone numbers and sells this data as a fraud prevention tool, called 'Intelligence API'. Per month, TeleSign says it "verifies over five billion phone numbers," which represents "half of the world’s mobile users", and "gives critical insight into the remaining billions."

The problem? Phone users that trust their mobile operators with their information are not aware of this scheme.

The lawsuit points out that the system is problematic also because TeleSign falls under US surveillance laws, which means that the US government can access the data. Sending European personal data across the Atlantic is technically illegal without a valid EU-US data transfer agreement. The old agreement, called the Privacy Shield, was scrapped in 2020 in part because the US laws were deemed too intrusive, and the existing privacy protections in the US not on par with the GDPR standards in the EU. The resulting legal vacuum has left many big tech companies like Meta facing hefty fines for continuing to transfer European user data to the US. In early July, the EU and US finally hammered out the details of a deal that should replace it, but its fate is still uncertain as it is likely to face legal challenges.

What data does TeleSign access to determine a reputation score?

Exactly how the reputation score is calculated is anyone's guess. On its website, TeleSign claims that the reputation score is assessed on various factors, but the exact methodology is proprietary. Some of the things TeleSign says it uses to assign a score to phone numbers are phone number data and analytics, data from third-party organizations that allow it to check whether a phone number belongs to a known fraudster, patterns in phone usage, frequency of usage, which can also indicate fraud (for example, if it is used every few minutes), and machine learning predictions.

Because the methodology is proprietary, there's no way to know how these things add up to a high or low trust score. Users can ask TeleSign for a copy of their data, and, according to the lawsuit, some have found they received a "medium-low” risk rating.

While users can obtain their data from TeleSign, mobile operators seem unaware that their customer data is being sent to TeleSign, according to NOYB.

In a nutshell, your access to a particular online service may be blocked due to an opaque privately-operated scoring system that assigns you a rating based on an arbitrary set of criteria and works behind the scenes without your knowledge.

Legal basis: what BICS and TeleSign say?

The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation(GDPR) lists six lawful grounds for processing personal data, namely consent, contract, vital interests, public duty, and legitimate interests. The latter is the most flexible, and it lets companies use data without asking the user directly. For instance, OpenAI uses "legitimate interest" as an excuse to collect and use publicly available personal information to train AI models like GPT, which powers ChatGPT. This justification is highly questionable, and OpenAI's habit of grabbing personal and other data from the Web has been met with a mounting pile of lawsuits accusing it of profiting from privacy violations.

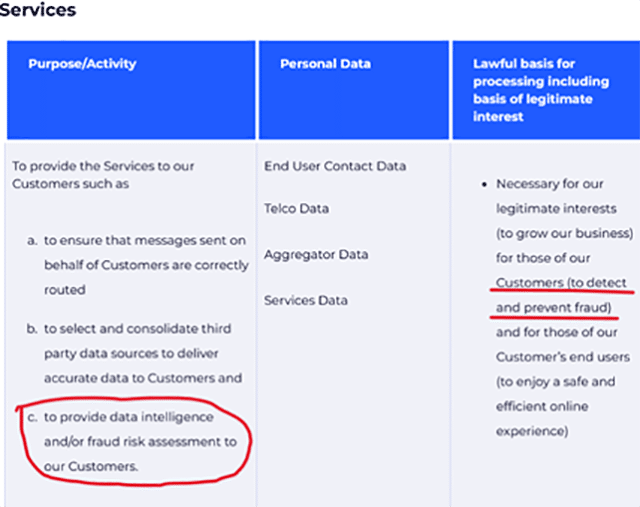

BICS and TeleSign both claim ‘legitimate interests’, specifically, detection or prevention of fraud as their legal basis of data processing.

Speaking to Le Soir last year, Proximus, which owns both BICS and TeleSign, said that all transferred data is "end-to-end encrypted" while telephone numbers "are masked to prevent individual identification." As for how it manages privacy risks stemming from transfer of data to the US, which by this day still lacks a federal privacy law, it says that it "has taken additional measures to prevent the identification of individuals should the data end up in the hands of an authority or should a data breach occur." But how these companies ensure the data does not fall into the wrong hands is unclear.

The lawsuit alleges that BICS and TeleSign's activities go beyond fraud prevention, and are disproportionate, mainly meant to generate revenue. In addition, BICS has never informed users of the data processing, which potentially violates its transparency obligation under article 14 of GDPR.

Something rings a bell?

What the TeleSign system does is basically evaluate your reputation based on your phone usage. It is not so different, at least in spirit, from another system that is often portrayed as something strictly nefarious and anti-privacy. In some ways, the TeleSign system is reminiscent of China's social credit system in that they both assess trustworthiness based on behavior data, and can reward or punish individuals based on this data. This should ring alarm bells for privacy-conscious users.

Of course, it would be a stretch to equate the activities of TeleSign and BICS with those of the Chinese government. First, because China's social credit system is a government policy, not a commercial product, and second, because it is much broader in scope, resulting in the tracking and scoring of individuals based on a wide variety of their online and offline activities.

How the system can negatively affect you

Despite assurances from Proximus, BICS and TeleSign, the data is not safe with them. There is the obvious danger in the data being processed in the US, where data protection laws are weak, while the safeguards proposed in the newly proposed US-EU transfer agreement have yet to withstand a legal challenge.The collected data could also be exposed by a breach or a leak, leading to identity theft. In addition, and perhaps most importantly, the system can deny services to mobile users based on their reputation scores, which are calculated without their knowledge and consent, and which they have no way of correcting, deleting, or challenging, simply because they are unaware of their existence.

What can you do

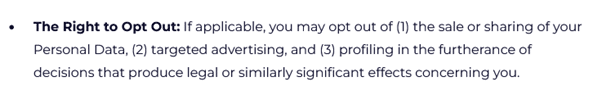

Thanks to NOYB exposing the practice, more people will learn about it and their right to request, rectify, and delete their data from TeleSign. This can be done through a form on TeleSign’s website. According to its privacy policy, it's possible to opt out of personal data selling and sharing, including for profiling purposes.

To avoid being profiled by TeleSign or similar companies, some general recommendations are to use multiple phone numbers for different purposes, or to use a virtual number instead of your real one for online services. For example, if you do cold-calling, you may want to have a separate phone for that, so you won’t be mistaken for a scammer and denied access to certain services.

A good rule of thumb is to be aware of the data protection laws and the ways you can benefit from them, such as by asking for the data that companies have on you and requesting its deletion. You may also want to take other measures to protect your privacy, including using a VPN, limiting the personal information you share online, and being careful with app permissions. These steps won’t stop phone-based profiling directly, but they will add an extra layer of privacy to your browsing.

Image Credit: Wayne Williams

Andrey Meshkov is a co-founder and CTO of AdGuard.