New Microsoft 'Morro' anti-malware will share competitors' security events

It's an argument we've seen before from Microsoft's competitors and opponents, as well as from many sensible observers: It may be unfair for the manufacturer of the operating system to leverage its customer visibility to advance a free software platform that cuts out commercial competitors. But there's another argument from opponents as well, many of them the same people: Microsoft should be responsible for the health and well-being of its customers' systems when the operating system is threatened, either through malicious use or from system defects.

It's an argument we've seen before from Microsoft's competitors and opponents, as well as from many sensible observers: It may be unfair for the manufacturer of the operating system to leverage its customer visibility to advance a free software platform that cuts out commercial competitors. But there's another argument from opponents as well, many of them the same people: Microsoft should be responsible for the health and well-being of its customers' systems when the operating system is threatened, either through malicious use or from system defects.

So what should it be? Today, for better or worse, the company staked a broader claim on the anti-malware market with the initial public beta release of Microsoft Security Essentials, formerly code-named "Morro." It's not the company's first free anti-virus product -- it first cut its teeth (and maybe cut some other parts along with them) with Windows Defender for Vista. And in the subscription service field, OneCare became notorious first for being substandard, and then for a public relations patch-up campaign that blamed the world at large for having been substandard.

Historically, Microsoft hasn't been able to get the ball rolling in this department. In fact, for well over six years now, Microsoft's anti-malware efforts have continually begun and begun again, dating back to the original incarnation of Security Essentials planned in 2003 for Windows XP.

What it's calling Security Essentials today is a piece of this and a piece of that: the core scanning engine from OneCare, along with the capability to share malware signatures in real-time with the Dynamic Signature Service originally intended for its Forefront commercial package, wrapped together with a front end that effectively substitutes for Windows Defender, and that looks slightly more like an XP product than a Vista product. But at the heart of the system is the first public test of an idea that was supposed to premiere with Forefront last April and didn't: a live database of security events compiled with the aid of perhaps as many as 20 partners.

What it's calling Security Essentials today is a piece of this and a piece of that: the core scanning engine from OneCare, along with the capability to share malware signatures in real-time with the Dynamic Signature Service originally intended for its Forefront commercial package, wrapped together with a front end that effectively substitutes for Windows Defender, and that looks slightly more like an XP product than a Vista product. But at the heart of the system is the first public test of an idea that was supposed to premiere with Forefront last April and didn't: a live database of security events compiled with the aid of perhaps as many as 20 partners.

The database is called the Dynamic Signature Service (DSS), and it's compiled using what's called Security Assessment Sharing -- part of a revised platform Microsoft put forth in 2007 code-named "Stirling." With SAS, anti-malware events logged by these partners' commercial software may be utilized in real-time by Security Essentials. Though the complete list of participating vendors has not been released, those who thus far have been willing to acknowledge their own participation include: Brocade, Guardium, Imperva, Juniper Networks, Kaspersky Labs, Q1 Labs, RSA, Sourcefire, StillSecure, and TippingPoint. (Some of these SAS partners are credited on Forefront's Stirling page.) Some you've likely heard of, others maybe not, though by sharing information with one another and with Microsoft, these firms could be giving each other a leg up against competition from "the usual gang," including McAfee and Symantec.

The sharing of events with the DSS requires the Security Assessment Sharing Agent, which for now is a part of other Microsoft server software such as Exchange Server -- it's not part of Security Essentials.

Still, the argument against the use the DSS goes like this: When Microsoft uses a high-powered feature to elevate the profile of an anti-virus service that it has already described as providing only basic features, but doing so for free, it could be provoking Windows users to accept substandard security rather than invest in commercial alternatives.

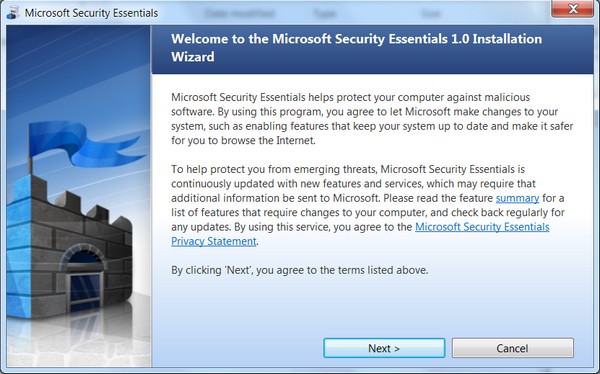

The initial message Security Essentials gives its customer is, "Trust Microsoft." As the installer program describes for itself, it may reset settings for Automatic Updates so that they are downloaded and installed automatically -- in other words, "full green" in the icon. Its message reads: "By using this program, you agree to let Microsoft make changes to your system, such as enabling features that keep your system up to date and make it safer for you to browse the Internet." It's the company's way of saying to customers, if you choose to go down this road, you're making the decision to trust Microsoft with the security of your operating system and files.

DSS is one of those ways, and now Microsoft will be opening up its database to select partners in exchange for them opening their databases in turn. Combining the resources of several companies, including independent engineers -- all in the spirit of "interoperability" -- could poke a lot of holes in that counter-argument.