Psst...Wanna buy a used Palm?

As rumors swirl around the latest chapter in Palm Inc.'s checkered journey from mobile darling to also-ran, I'll resist the urge to place bets on which company or companies will be making an acquisition play. It almost doesn't matter who buys Palm at this point. What matters is what that buyer does with Palm afterward, and how any acquisition would affect that company's existing mobile strategy.

As rumors swirl around the latest chapter in Palm Inc.'s checkered journey from mobile darling to also-ran, I'll resist the urge to place bets on which company or companies will be making an acquisition play. It almost doesn't matter who buys Palm at this point. What matters is what that buyer does with Palm afterward, and how any acquisition would affect that company's existing mobile strategy.

For quite some time, it's been obvious to everyone but Palm that it would eventually need a white knight. Palm seems to have finally clued in, as Bloomberg is now reporting that the mobile device vendor has engaged Goldman Sachs and Qatalyst Partners to find a buyer.

I need a hero

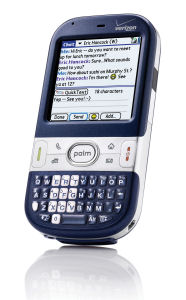

Although I've been predicting this for a while, I admit feeling more than a little sad that the end of Palm's road is within sight. This is, after all, the plucky outfit that popularized the personal digital assistant, and had geeks everywhere taking notes in Graffiti. Unfortunately, Palm went from leader to follower when we ditched standalone PDAs for connected smartphones. Sure, the Treo 600 was a great piece of work, but after hawking essentially the same product for over six years -- a long time in any business, but a hopeless eternity in tech -- Palm was clearly yesterday's news.

This latest twist in the company's history is a stark lesson for anyone else in tech: Take your eye off the ball once, and you risk eventually losing the game.

Palm did itself no favors by continually, and seemingly endlessly, remaking itself with spinoffs, rebrandings, acquisitions, and restructurings. The company spent so much time on its corporate image that it forgot its product image. Remaking Palm Inc. rather than Palm products diverted corporate attention from rebuilding the foundation of products that, ironically, could have sustained the image of Palm Inc., or PalmSource, or PalmOne, or whatever. Developing compelling new products that consumers and businesses wanted, and building relationships with the broader stakeholders who would have added ongoing value to those products, should have been PalmOne's job #1.

All the corporate gymnastics also distracted Palm from the not-so-subtle shifts that were redefining the industry it had practically created. Specifically, as platform success became ever more dependent on factors way beyond just hardware, Palm continued to bet the farm on just hardware. Instead, it should have been investing in building a community of developers who would have made a webOS-based device worth more than the sum of its parts.

Great hardware. Not-so-great everything else.

The Pre, introduced at CES 2009, was a technological home run. Its just-unique-enough design and slick webOS operating system should have been enough to get consumers out of bed in the middle of the night, and lined up around the block before dawn. And indeed, there were some developers who started lining up at the front of the queue; trouble was, Palm didn't send anyone over to that line to start selling tickets. It assumed developers who either created the first vibrant mobile software market years earlier, or at least remembered Palm OS' success, would naturally return to the fold. Unfortunately, Palm left its legacy products in market for so long that by the time the new stuff was ready, the developers had migrated elsewhere.

Palm's problem was, and is, apps. Back in the era before Internet distribution, the old Palm OS platform boasted a library of over 4,000 third-party applications. By comparison, the Palm Pre launched with barely a dozen-and-a-half third-party apps, at a time when Apple was rewriting the criteria for mobile platform success. When the Pre was announced, Apple's App Store had 15,000 titles. By June, when the Pre began to ship, Apple boasted 50,000 titles. Today, it's up to 185,000 with no end in sight.

Palm? It's just cracked a thousand titles.

Not that I believe that total app volume is the ultimate driver of platform success. It isn't. Apple's App Store is home to plenty of frivolous titles that aren't even worth a chuckle or two around the office water cooler. A smaller number of more substantive apps could just as easily sustain a healthy and vibrant smartphone platform. But image is a big thing in the minds of developers whose futures depend on which platform they're most associated with.

Just ask anyone today who's known in the coding community as the iPhone developer who builds apps for webOS. You've seen the good kids in high school who just can't get the more popular ones to notice them because, although they wear the right clothes, they signed up for chess club rather than track. Well, good developers can't get noticed in any field when they're associated with a single platform that lacks traction. Palm's App Catalog never had a chance, because the only developers willing to risk everything on the once-and-no-future king were die-hards. Everyone else settled on developing for the sure-thing iPhone or, increasingly, Android.

Look beyond the buyout

Whoever acquires Palm (press rumors mention HTC, Lenovo, Dell, and even Apple and Microsoft) will gain access to not only a fairly leading-edge set of hardware designs and a promising mobile OS, but also a broad range of patents and related intellectual property.

The key to success for that suitor will be to avoid sinking new resources into designing and releasing yet another brand new, killer phone. Palm did not fail on the hardware or OS side -- its offerings are already as good as they get. Instead of putting its eggs into hardware development, Palm's suitor would do well to actively target developers now grappling with Apple's our-way-or-no-way approach, or Google's fragmented-landscape mentality. Successful as these solutions are, they're not perfect -- and more importantly, neither is an ideal fit for every developer.

There's room for an alternative player in the still-fast-growing mobile landscape. Developers continue to hold out hope for a successful mobile platform sustained by a company that understands the way they do business, rather than building up self-sustaining provisos in its developers' contracts. Hope is a powerful ingredient. Used well, it can produce something new and better called loyalty. But it won't do that on its own.

Carmi Levy is a Canadian-based independent technology analyst and journalist still trying to live down his past life leading help desks and managing projects for large financial services organizations. He comments extensively in a wide range of media, and works closely with clients to help them leverage technology and social media tools and processes to drive their business.