2000-2009: Microsoft's decade of shattered dreams

This will be the toughest commentary I likely will ever write about Microsoft. It is toughest for me to compose because I see what Microsoft could have been in 2009 from where it started in 2000. It is toughest on Microsoft, more than anything I may ever write again about the company.

I dedicate this seemingly harsh post to all the Microsoft employees that privately have complained about management problems -- not because they were mad or resentful but because they desperately wanted to fix the problems. They spoke to me in confidence out of their love for Microsoft. I apologize for not speaking up for them before. I do so today, as reflection on the past to shed light on future actions. The decade 2010 could be better if Microsoft learns from its mistakes.

Long on Vision, Short on Execution

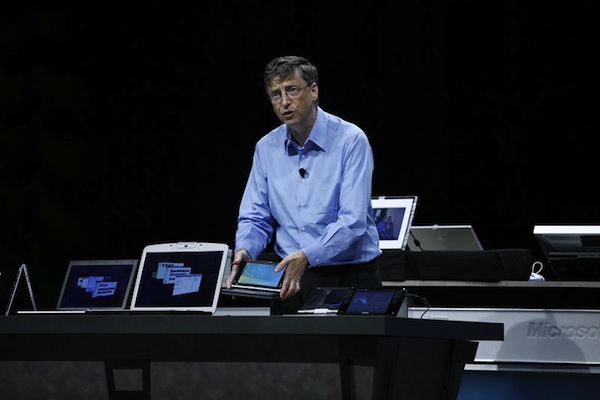

Microsoft executives and product managers -- Chairman Bill Gates, above all of them -- showed great technology vision for the new millennium. The company was right about so many trends to come but, sadly, executed poorly in bringing too many of them to market. Microsoft's stiffness, perhaps a sign of its aging leadership, consistently proved its foible. Then there is arcane organizational structure, which has swelled with needless middle managers, and the system of group competition -- and in the new century compensation -- that worked well for a growth company but not one trying to manage mature markets.

Some of the many, many examples of good Microsoft vision gone bad:

Ebooks -- Microsoft released its ebook reader software in early 2000, but didn't stick with the strategy. So it would be Amazon and not Microsoft that would fulfill the ebook vision.

HailStorm -- Microsoft had the right idea about consumer Web services, announced in early 2001 and killed about a year later. Today the Web is all about consumer Web services with Facebook leading the way.

Digital music -- Microsoft saw the potential for digital content, starting with music, long before Apple. But Microsoft chose to drive usage through digital rights management tied to Windows when the focus should have been digitizing the content consumers already owned on CDs. Apple got it right.

NTFS -- The new data store extended the Cairo vision abandoned in the mid 1990s. Microsoft was right about storage's importance but gave up on a vision that would have made Windows and Windows Server the center. Instead, Amazon took storage to the cloud, and Microsoft is still playing catch up with Azure, which goes live later this week.

Origami -- Microsoft was right that consumers and business users would want a small, low-cost tablet computer. The company understood the right price, under $500, which its partners couldn't deliver. But Apple delivered the right kind of touchscreen device, with iPhone in June 2007.

I could easily rattle off twenty 2000-2009 visionary projects that Microsoft started, only to later cancel or fumble. It's a maddening reflection, because there is so much promise gone bad.

Microsoft Should Have Fired all the MBAs

The new millennium's first 10 years is really Microsoft's lost decade. It is a decade of shattered dreams. Microsoft 2000-2009 is a casebook study why no company should allow its ranks of MBAs to swell too large. The company's 5,000-plus layoffs should have sacked 95 percent of the MBAs rather than the many good, hard-working employees sent packing. I repeatedly hear Microsoft employees privately complain about there seemingly being one MBA -- or lawyer -- on campus for every other employee.

I'm so hard on the MBAs (and lawyers), because Microsoft's problem during 2000-2009 wasn't lack of the aforementioned vision but of execution. Somebody had a good idea, Microsoft started to bring it to market and the project was cut clearly for some business or legal reason. A close examination shows a common trend: Repeated starts, stops, realignments, more starts and major directional changes or closure of many good projects. It's like some business dude spent too much time plowing through spreadsheets when he or she needed to get out into the real world.

That's another problem -- and I've heard about it so many, many times from Microsoft employees: Most every technology decision must be justified by some data point. No company spends on research like Microsoft -- third-party analyst studies, Microsoft collected data and seemingly bazillions of focus groups. During this decade, justification by data hasn't worked well for Microsoft visions becoming reality.

Microsoft's two failed acquisitions -- Yahoo and YouTube -- show how MBA thinking and over-reliance on data analysis proved fatal. About six months before Google paid $1.6 billion to buy YouTube, Microsoft passed on about a $500 million acquisition opportunity. Ballmer later said that Microsoft conducted a buy-versus-build analysis and decided it would be more cost-effective to create a video streaming service. Microsoft launched MSN Soapbox, which flopped and later failed. YouTube became one of the hottest properties on the Web and huge driver of Google search traffic. Just for search alone, YouTube would have been an invaluable service for Microsoft.

The failed nearly $45 billion Yahoo acquisition is another example of MBA-thinking and over-emphasis on data analysis gone wrong. Microsoft wrongly assumed that combined with Yahoo its search share would reach 30 percent in the United States and higher in some other markets. The same reasoning applied to the search deal Microsoft eventually cut with Yahoo --- and more: Search scale would allow Microsoft to improve search accuracy. The reasoning is fundamentally flawed, as recent ComScore search share numbers indicate: Microsoft will cannibalize rather than combine with Yahoo search share. Meanwhile, Google will continue its search gains and extend them to mobile devices.

Overfeeding the Cash Cows

By the same kind of MBA logic, Microsoft should do nothing really new. All future innovation should be tied to the cash cow products -- Office and Windows. Where Microsoft did extend, in server software, it tied countless features to Office, most aggressively starting with the 2003 release cycle. What would SharePoint have been if not for Office, or visa versa, after v2003?

Related: Focus on competitors rather than innovation really defined Microsoft 2000-2009 business and technology practices. It's one reason why Microsoft got blindsided by Apple and Google in the handset market. Microsoft relied too much on data supporting its enterprise handset strategy, meanwhile working to match BlackBerry e-mail features; no coincidence, features that would benefit Outlook and Exchange Server. Microsoft took Windows Mobile development down the wrong path and now struggles to return to the fork in the road.

Innovators focus on the customer and creating something that people didn't know they needed. Apple has done this repeatedly over the years. Creating something people didn't know they needed is an axiom of good design and not easily achievable when the focus is on responding to competitors, which are a distraction. Google is Microsoft's biggest distraction. Microsoft leadership recognized Google to be a competitor long before it ever was. But Microsoft followed Google rather than leading with innovation. It's a stupid, sorry mess.

Where Microsoft defied the data or business school common sense, success followed. Xbox is the textbook example, and it should be the model for other Microsoft projects. Microsoft set out in the game console market with the expectation of losing money for many years. That investment, coupled with good management decisions and vision, paid off for Microsoft. Who would have really thought in 2001 that in just a few years Microsoft would dethrone Sony in the game console market? Similarly, Azure's potential is Microsoft's investment in it for long-term gain. The approach defies typical business school logic, which for public companies too often emphasizes short-term, quarterly goals.

Short-Term Goals are a Long-Term Problem

Short-term goals are Microsoft counterculture. Gates built the business by making fast, short-term tactical decisions without sacrificing longer-term visions five to 10 years out. Long-term technology planning has long been a core Microsoft strength. This mix of tactical and long-term business operations made Microsoft one of the most successful companies of the 1980s and 1990s. But in the early 2000s, while long-term vision remained, MBA assessments and legal considerations ruled too many short-term decisions -- and they killed some visionary stuff, too.

In looking at the decade, the technology leadership made one major frak-up -- and it was huge: Windows Vista. Jim Allchin and his team fraked it up, totally. Windows Longhorn (e.g., Vista), and all those features promised during PDC 2003 and later dumped in 2004 and 2005, is a textbook case of product management gone awry. The problem was one of too much vision and not enough short-term execution.

Longhorn truly would have been a transformative operating system. If released in 2005 as envisioned, Longhorn would have shaped the technology landscape towards a different direction than it has gone today. Almost certainly, Microsoft would have assured Windows' computational and informational relevance for much longer, reigned in developers who left for the Web, held down Mac market share to a couple percent and slowed down Google's advances. As I've repeated so many times, nearly all the social media changes now underway and Google's rapidly gaining Web dominance started in 2006.

Something else did happen in 2005. Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer reorganized the company, placing business and marketing people in key leadership positions, including the three newly created presidents. For a company of technology geeks, marketing leaders were something close to freaks -- or so I've heard from a number of Microsoft employees.

Is that the end then, for Microsoft? Hardly, despite the econolypse sapping sales. In 2009, Microsoft promoted two technologists, Bob Muglia and Steven Sinfosky, to be presidents over Server & Tools and Windows & Windows Live divisions, respectively. Outsider and technologist Stephen Elop has competently run the Business division since assuming the president's role in early 2008.

Meanwhile, Microsoft product managers started using blogs and social media tools to get more in touch with customers and enthusiasts and to better incorporate their feedback into the product development process. The quality of this effort dramatically improved in 2009.

But "the road ahead," using the title of Gates' 1995 book, is full of potholes. Microsoft needs to cut the middle management (five layers of managers is five layers too many), layoff or demote many of its MBAs, put more geeks in charge of major projects and focus more on long-term innovation rather than short-term goals or reaction to competitors. Microsoft isn't a lost cause. It's simply a company that lost its way.