Developers, save us from the Microsoft undead

More software developers should follow the lead of Adobe and Skype, which have abandoned Windows Mobile -- what Microsoft now calls Windows Phone Classic. The mobile operating system already was brain dead, even with, according to Gartner, 15 million unit sales in 2009. The heart pumped out licenses, but there was no brain activity to keep the platform going. Windows Mobile flatlined, and it's about time that some Microsoft developers admit it. Others should get over the denial and do the same. Microsoft doesn't have the courage to pull the plug. But smart developers can.

Skype's move was quite audacious -- pulling the Windows Mobile version of the telephony software from download. Those WinMo users with Skype can continue using it. Adobe is doing something different. It's shifting Flash 10.1 development to Windows Phone 7 Series, sidelining any Windows Phone Classic version. Both developers acted wisely. Microsoft may have kept Windows Mobile on life support by the Classic renaming, but the operating system has no real future. There's little reason for hardware manufacturers to release new Windows Phone Classic handsets or for anyone to buy them -- with Windows Phone 7 Series phones coming late in the second half of the year.

Adobe and Skype have set an example not just for other developers but for Microsoft and its customers. Microsoft has for too long made backward compatibility a top development priority, and the approach holds back platform development. Microsoft's willingness to prioritize backward compatibility makes it too easy for large enterprises to run older software versions seemingly forever.

That's why I'm proud of Google and other developers that are saying no to Internet Explorer 6. The browser is ancient by computing years. I calculate computing years as actual years divided 1.5 (Moore's Law) times 7 (dog years), which makes the browser more than 44 years old. By just dog years, IE6 would be a rickety nearly 70 years old. Antiquated software like IE6 has no place on computers anywhere, particularly considering how different the Internet is today than in 2001. Nine years ago, malware making was still more malicious than criminal. Now it's a bloodsport. IE6 isn't young enough or tough enough.

Enabling Bad Customer Behavior

Then there's Windows 2000. In this era of massive layoffs, someone's head should roll in organization running Windows 2000 anywhere. But, of course, Microsoft enabled the bad behavior by backward compatibility and nearly endless life support -- eh, lifecycle support. But Microsoft plans some massive life support plug pulling this year -- although not nearly enough of it, I assert. Windows Vista gold code support ends on April 13. Support for Windows 2000 and Windows XP Service Pack 2 end on July 13. I wish these operating systems well in the afterlife, if that were possible. They will linger still, as ghosts, and for that Microsoft bears some responsibility.

Microsoft's approach to fighting piracy includes preventing presumed pirated Windows copies from downloading important updates. Legitimate Windows XP or Vista customers can apply a service pack and let their aged operating systems live another day. But those expired, pirated versions will became the Windows undead. Malware writers can use the Windows undead to haunt the Internet with phishing email or, among other nefarious activities, to use Trojans to control living Windows. Call them the possessed.

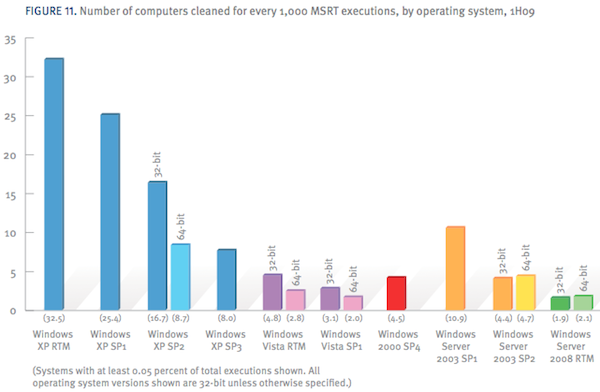

Perhaps it's telling that the Honeynet Project uses unpatched Windows 2000 and XP systems to bait botnets: "This system is thus very vulnerable to attacks and normally it takes only a couple of minutes before it is successfully compromised." Microsoft's own data (see chart) shows that older Windows versions are more vulnerable to exploit than newer ones or those older ones with newer service packs. How strange, or perhaps revealing, that Microsoft's twice-yearly Security Intelligence Report ignoresthe topic of unpatched pirated Windows versions.

But older, unpatched operating systems are only part of the problem. There is client software, like the aforementioned IE6, or Office. Microsoft anti-piracy tactics can prevent these products from updating, too. Last year, SANS identified to two serious "cyber security risks," one related to client software. Even when updates are available to legitimate customers, they're too slow to apply them. According to SANS: "On average, major organizations take at least twice as long to patch client-side vulnerabilities as they take to patch operating system vulnerabilities. In other words the highest priority risk is getting less attention than the lower priority risk."

But all of this would matter less if more businesses or consumers used newer software -- and if Microsoft enabled good behavior by shortening lifecycle and backward compatibility support.

Developers: The Undead Slayers

Developers have the power to change Microsoft's behavior. They demonstrated this with Windows Vista, which launched without broad application or hardware driver support. By holding back on Vista, developers contributed to early customer bad experiences using the software. Developers should use this power differently -- to get businesses and consumers off older Microsoft software versions. Adobe and Skype (with Windows Phone Classic) and Google (with IE6) show the way for other developers. If Microsoft can't pull the plug. They should.

Microsoft is ready to be helped by developers. The company seems near acceptance that prolonged life support is bad business. The Windows XP-to-Windows 7 upgrade process is example. For once, Microsoft put the experience of the newer thing before compatibility with the older thing, by making XP customers do a clean install to Windows 7. Yes, the approach caused customer migration headaches, but Microsoft's priority was in the right place.

Developers also can help kill off the Windows undead, by removing applications -- particularly Web browsers -- for older operating systems. Sure, there are too many torrents to feed the Windows undead with older software, but developers can make a start by officially yanking their stuff.

Security is one consideration. Usability is another. If there's a Moore's Law for software, it's coming from the Internet. New connected Web services and applications pop up every week. Is the better (and safer) experience going to come from IE6 running on Windows 2000 or IE8 (Chrome, Firefox, Opera or Safari) running on Windows 7? The answer isn't rocket science. The scourge of older software creates barriers to innovation.

Look at how Apple handles iTunes or iPhone OS. The upgrades are forced during X time period. For iTunes, users are prodded to upgrade until at some future time they can no longer access the music store without a newer software version. For Mac OS X 10.6 (aka Snow Leopard), Apple encouraged Leopard users to upgrade by $29 pricing -- or $100 less than previous versions. Microsoft does some of this forced upgrading with connected apps like Windows Live Messenger. But, overall, the company's approach favors backward compatibility until the software atrophies on life support.

Pull the plug, developers! Because Microsoft won't do it soon enough otherwise.