Apple's Mac App Store fundamentally changes PC software usage rights

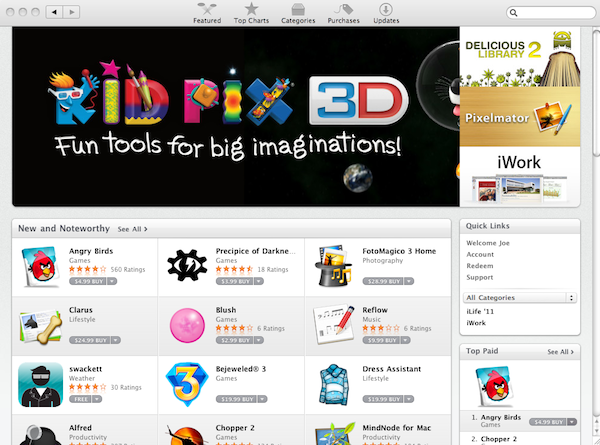

Earlier today, Apple officially launched its application store for Macintosh, with about 1,000 free and paid applications available. Snow Leopard users download the Mac OS X 10.6.6 update, and the store is included. But people using the software are in for a change. Consumers typically buy software by machine. Those people buying from the Mac App Store purchase by person. The software is attached to an identity. This is a dramatic departure from how consumer software is typically licensed.

Licensing agreements typically restrict installation on one PC, sometimes two or even three. If a consumer goes into a store and buys, say, Microsoft Office, the purchase ultimately is tied to a computer. For years, Microsoft took machine purchases on trust, but in 2001 added product activation to Office and later Windows. Office 2011 is the first Mac version of the productivity suite to require product activation, which essentially locks the software to a computer. Not a person. Similarly, when a new PC ships with Windows, the license is tied to the machine not the buyer.

The problem with machine licensing is piracy. The licensor expects to be paid for additional software installations, but many, probably most, consumers buying software for one machine don't see a problem with putting it on others. Microsoft developed product activation to prevent this activity, which it calls "casual piracy." Other software developers, Adobe among, use similar activation mechanisms.

Thinking Differently about Software Licensing

The Mac App Store changes the paradigm and usage rights associated with it. Buyers use an existing Apple ID (usually from iTunes) or create another. Software purchases are tied to that identity, not the PC. If a licensee buys another Mac, he or she can redownload the software using the same ID without paying again. People buying music from iTunes or apps for iPad, iPhone from iTunes are used to this kind of identity approach, but it's not common for computer software.

But uncommon doesn't mean non-existent. Some software developers offering digital downloads use an identity approach. Adobe does this. Customers set up an Adobe ID to which the purchase is tied. This allows the buyer to redownload the software and to reactivate it. But the process feels restrictive, because there are really two rights protection mechanisms -- the ID and password to download the software and product activation when entering a serial number.

Will History Repeat in 2011

Apple's approach is simpler and feels familiar; repeating history, the company doing in 2011 what it did in 2003 -- fundamentally changing content licensing policy. Before the April 2003 launch of the iTunes Store, major labels applied different licensing rights to digitally downloaded music, confusing consumers and deterring purchases. There were restrictions on CD burning and listening to music on different computers. Apple negotiated uniform rights for all music, and they were generous -- up to three PCs (later extended to five) and multiple CD burns from a single playlist. All this started on the Mac, which was a safe experiment for record labels considering Apple's tiny PC market share.

Apple fundamentally changed how rights-protected digitally downloaded music is licensed, particularly after iTunes Store released for Windows in October 2003. One person in a household could buy music and make it available to others simply by authorizing the computer using the Apple ID associated with the music purchase. The same principle applies to Mac App Store but with a slightly different process. Each application is authorized using the Apple ID when downloaded -- like the iOS App Store.

The rights are hugely generous and more in line with consumer expectations: That they buy software once and use it anywhere within the household. According to the Mac App Store FAQ: "Apps from the Mac App Store may be used on any Macs that you own or control for your personal use." Emphasis: Any. Not three Macs, or five or any other number. Considering that most software is licensed for one PC -- although many developers probably don't have realistic expectation of 1:1 installation -- any is quite a change. Something else: applications purchased from the store do not require activation keys, registration numbers or serial numbers. Only the Apple ID and password are required.

Your Identity is Your Right to Generous Rights

Identity licensing isn't new, and it's widely used for content licensed for other purposes or mobile devices. Content streamed from Hulu Plus or Netflix uses an identity scheme. E-books stores like Amazon Kindle tie purchases to an identity. But rights are restrictive compared to Mac App Store. Amazon and Barnes & Noble offer limited, 14-day lending rights for e-books. This can be somewhat circumvented by having all the people in a family use the same Kindle account, since Amazon licenses the content for on up to five different devices associated with the account. But it is nevertheless restrictive. Apple's approach is better, and it could quite possibly change usage rights elsewhere, as iTunes did in the mid-Noughties. The place for Apple to start is in its backyard, securing more generous rights for e-books purchased from iBookstore.

The question developers and other licensors surely must ask: How will we get paid? The one software application-to-one computer approach theoretically means the developer makes money on each installation. But, c`mon, who really buys three copies of software for three home computers, unless forced to (say, by onerous product activation)? On the other hand, a consumer might pay once at the Mac App Store and use the application on four or five computers. What developer wants to get paid once when there is chance to collect several times?

To both scenarios, I say this: The Mac App Store provides a secure place where people can easily find the software; where they will pay for it at least once and where digital rights management technology deters (or prevents piracy). It's better to sell something than nothing at all -- and if the iOS App Store is any indication most developers will sell their wares.